Handsome is a man, a woman, but rarely a child. Handsome is a Hemingway heroine, “built with curves like the hull of a racing yacht.” Handsome is Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant, and every member of the Handsome Men’s Club. Handsome can be equine, old girl, full of vim and vigor. Handsome is well-constructed, sturdy, but not without refinement. Handsome can be gray-haired and possibly carrying a cane. Handsome is the default for a man, but particular for a woman. Handsome, coming from a misinformed speaker, can be an insult. Handsome is a craft.

Handsome, etymologically speaking, is easy on the eyes. It originated from the old English hand and some, meaning "easy to handle," morphing into “of fair size” by the 1570s and making a quick transition into “good-looking” only a few years later. Until the 20th century, men and women were both described as handsome—good-looking, attractive—with regularity, with little difference in meaning. Rather, little general difference in meaning: As with so many words we use to describe women, as early as 1783 writers were eager to parse out what exactly makes a woman handsome. “By a handsome woman, we understand one that is tall, graceful, and well-shaped, with a regular disposition of features; by a pretty, we mean one that is delicately made, and whole features are so formed as to please; by a beautiful, a union of both,” writes John Trusler in 1783's The Distinction Between Words Esteemed Synonymous in the English Language. “A beautiful woman is an object of curiosity; a handsome woman, of admiration; and a pretty one, of love.”

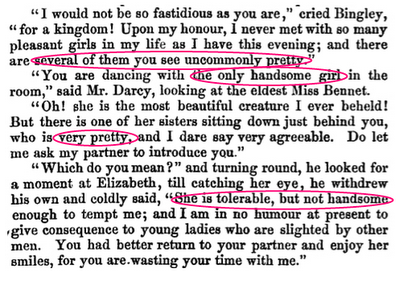

Trusler may have been prescient here, for the case of pretty vs. handsome pops up again in 1813, with Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. At the grand ball, after Mr. Darcy protests to his confidant Mr. Bingley that there aren’t any good-looking women to dance with, we have the following exchange:

The one who is deemed merely “pretty” is, of course, Elizabeth Bennet, whom we’ve already learned is “not half so handsome” as her sister Jane. Elizabeth gets the guy in the end—but only after it’s been made clear that prettiness plays second banana to handsomeness in looks while ultimately reigning victorious in love. “Austen portrays the ‘handsome’ rival [as opposed to] her own ‘pretty’ heroine—as the old woman of parts, seen now as all too predictable,” writes Ellen Zetzel Lambert in The Face of Love: Feminism and the Beauty Question. “However virtuous...Austen’s ‘handsome’ woman is always condemned to play the other woman, the ‘pretty’ woman’s foil. Often an older sister or an older-sister surrogate, hers is the beauty that can be appraised by the judging man.” Today we champion the idea that Austen meant for us to root for the plain girl over the beautiful one, but in fact, on paper, we’re rooting for the pretty one.

Of course, Austen’s use of handsome wasn’t necessarily shared by all. Not twenty years after Pride and Prejudice’s publication, The New York Mirror proclaimed in 1832 that “A handsome woman is handsome only in one way; a pretty one is pretty as a thousand.” The two ideas aren’t necessarily at odds, but throughout the book we see Jane as having an uncommon physical beauty, while Elizabeth's beauty is revealed through her quick, intelligent eyes and graceful manner—hardly the cookie-cutter gal that the Mirror gives us.

In mid-century, the question of age and the handsome woman was introduced. The handsome woman had previously not been grossly restricted by age—our heroine’s mother in Pride and Prejudice is described as being “as handsome as any of” her teenaged daughters. (On the flipside, in a 1919 congressional investigation of Emma Goldman’s role in “Bolshevik Propaganda,” the answer to “Is she a handsome woman?” is “No, she is not... She was a rather good-looking woman when she was young.” At 50, Goldman was too old to be handsome.) Age still isn’t necessarily a defining factor of the handsome woman, but it’s a consideration—and not in the way it was for Goldman. Handsome is a decent indication that the woman being spoken of isn’t necessarily graced by the bloom of youth. Life magazine, 1951, on Mary McCarthy: “She is a handsome woman of 51.” New York, 1968, on La MaMa founder Ellen Stewart: “She is an exceptionally handsome woman in her forties.” Edward Albee describes the titular role of his 1980 The Lady From Dubuque as being a “handsome woman”; 64-year-old Irene Worth originated the role. Theologian Harvey Cox put a fine point on the difference between the beautiful woman and the handsome one in The Seduction of the Spirit, 1985, when describing his grandmother, “A large, handsome woman reputed to have been a famous beauty in her youth.”

For a possible reason as to the gradual link between handsomeness and age, we’ll turn to Urban Dictionary, often a source of foul terror but on occasion spot-on: “Handsome woman: A woman with the kind of refined beauty and attractiveness that requires poise, dignity, and strength of mind and character, things that often come with age.” Dignity comes up again in the classic definition of handsome women in the Oxford English Dictionary: “Striking and imposing in good looks rather than conventionally pretty.”

It’s this—striking, imposing—that explains why we still use handsome for men as a general synonym for good-looking, while we reserve it for a particular type of good-looking woman, even if we can’t quite agree on what type that might be. With the exception of cherub-faced cutie-pies, good-looking men of many stripes are routinely referred to as handsome: classically good-looking George Clooney, of course, but also fine-featured Ryan Gosling, bushy-browed Clive Owen, chiseled Brad Pitt, manly-man Javier Bardem, smoldering Taye Diggs, or Johnny Depp, who was once described by a fellow I knew as "required by law to be considered good-looking by everyone who has ever lived." For good-looking women, handsome is a descriptor; for good-looking men, it’s the descriptor.

The traditional rules of masculinity dictate that we’ll take our men striking and imposing as a default, just as we’ll take our ladies demure. We also describe men as beautiful, hot, cute, and good-looking, just as we do with women, but beneath most of these (with the possible exception of cute) lies an assumption of the strength and fine construction that’s already built into the default definition of handsome. The rough equivalent of a default compliment for women—beautiful—can imply a sort of divine harmony, a grace that must be inspired, not constructed. We want our men built, our women magic. The craft of handsomeness keeps it available to any woman or a man given a good set of genes. But it's only women whom society requires to go above and beyond fine construction into the realm of beauty.

I’ve grown to rather like handsome, though I didn’t always; I used to see it as lacking a feminine delicacy I wanted to be seen as possessing. Certainly I’m not alone: “A handsome woman. Did he honestly think that was flattering?” writes a character in Stephanie Grace Whitson’s Sixteen Brides, and hive-mind sites like Urban Dictionary and Yahoo Answers are rife with confusion on the matter. “Not conventionally pretty,” says one commenter; “May be either slightly attractive or slightly unattractive, but not to be mistaken with ugly,” says another. The less kind interpretations of handsome might still accurately apply, but over time I’ve begun to think of handsome as implying a sort of health and vigor I’d rather possess than delicacy. Handsome garners an admiration that needn’t be about lust or attraction, more about general appreciation. I might be warming to it in part because of age: At 35, while I’d like to think the bloom isn’t entirely off the rose, handsomeness is something that, with luck, I can look forward to for decades to come. Because of its breadth of connotations, it’s a term we can use to pique interest—in fact, at its best, the handsome woman may have an allure that the beautiful one might not. “She is gloved to ravish. Her toilet is of an exquisite simplicity. She has the vivacity, the fashions of an artist,” writes Mary Elizabeth Braddon in her 1875 novel Hostages to Fortune. “Permit, monsieur, it is not so easy to describe a handsome woman. That does not describe itself.”

______________________________________

For more Thoughts on a Word, click here.