Vogue stopped using bird models in 1921.

Several years ago, after a long day at the magazine I was freelancing for at the time, I hailed a cab and cried the whole way home. The chief cause of the crying was the last task I’d had to do at the office before departing for the night: Communicating to the art department that a top editor wanted to digitally slim a celebrity whose former battles with anorexia were well-documented in the press. Transcribing her request onto the circulating page proof, every stroke of every letter felt like it was being scratched upon my skin. I hated that anyone would look at this particular picture of the (trim, lovely, recovered) celebrity and want it trimmer still, I hated that it was part of my job to communicate this request, I hated that the editor was so high up as to make it improper for a lowly freelance copy editor to question her, I hated that the people reading the final product wouldn’t understand all the labor that goes into making beautiful people look beautiful on the page. Most of all, I hated that the celebrity might look at the story, spot the digital manipulation, and yearn for her days of hunger.

I hated it.So you would think that I’d be thrilled about Vogue’s recent announcement that they are no longer going to work with models who appear to have an eating disorder, will encourage designers to consider their practice of unrealistically tailored sample sizes, and will be “ambassadors for the message of healthy body image.” All 19 global editions of the world’s leading fashion magazine signed on to the pledge, this after an international flurry of other body image actions in the world of high fashion: Italy and Spain’s leading fashion coalitions banned models with BMIs deeming them underweight, and in March Israel recently passed a law doing the same. And indeed, I felt a wash of righteous joy when I read about the announcement: I mean, this is

Vogue we’re talking here.

Vogue! The emblem of why the fashion world is so often hostile to women’s bodies, the embodiment of the severe impact the thin-young-and-beautiful imperative has on women worldwide. Let’s be clear: This is a good thing. But for the reader, it’s not as good as it seems.

The impact here

appears to be significant, yes.

Its largest actual impact is on the labor force in question: In addition to no longer working with models who “appear to have an eating disorder,”

Vogue will not work with models under age 16 (and will ask casting directors to check identification), implement mentoring programs for mature models to give guidance to beginners, and encourage producers to provide privacy and healthy food backstage. Modeling is precarious work, a fact often overshadowed by its glamour in the public eye; for

Vogue to publicly acknowledge that its success is partially built upon the backs of young, precarious laborers, often émigrés from developing or unstable nations, does a real service to those workers, and that fact shouldn’t be lost.

It’s the last item on

Vogue’s six-point list that nags at me:

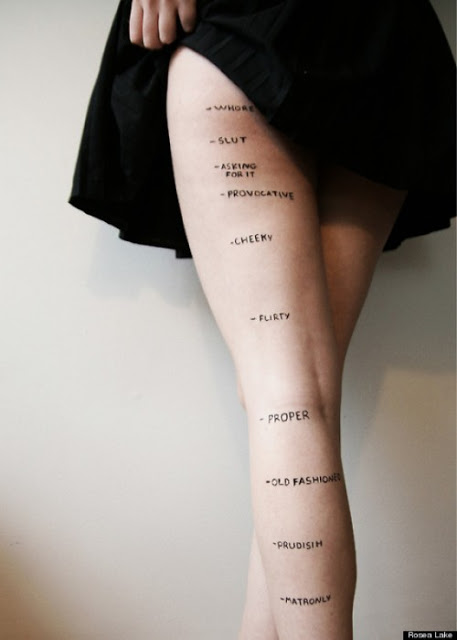

We will be ambassadors for the message of healthy body image. To herald Vogue as a game-changing ambassador of healthy body image is to forget that fashion photography is specifically designed to elicit a response—yearning—within us, and few things in our culture inspire yearning like thinness. To point out the obvious: Thinness will never disappear from

Vogue’s pages, only ill, underage models. Fashion photography is transportive, both real and unreal. The point for the reader has never been to be able to actually imagine ourselves in the photograph. Let the fashion still lifes do that; we can step into that empty dress, slip our arms through that stack of bracelets. The point of fashion photography is to synthesize distance and reality as we recognize it: It has to be close enough to what we recognize as real to trigger our response, but far enough away to make sure that response leaves us wanting, not contented. This is what fashion photography does; this is what makes it compelling. Longing built into its very function.

“The history of photography could be recapitulated as the struggle between two different imperatives,” writes Susan Sontag in

On Photography. “[B]eautification, which comes from the fine arts, and truth-telling, which is measured not only by a notion of value-free truth, a legacy from the sciences, but by a moralized ideal of truth-telling, adapted from nineteenth-century literary models and from the (then) new profession of independent journalism.” Fashion magazines epitomize both of these imperatives: Grace Coddington’s magnificent styling certainly falls into the realm of the fine arts, but

fashion magazines are always ultimately selling and promoting products that actually exist and are for sale—that is, they have an amoralized ideal of truth-telling. (Not that selling is without morals, but the sort of truth that advertising purports is quite different than the sort of truth we get from photojournalism. A seller’s intent, even if it’s a positive one, doesn’t stem from morality.) Even if few readers of

Vogue are actually able to purchase the clothes on its pages, they can buy the fast fashion knockoffs; they can be inspired by the looks on the pages.

And, of course, they can be inspired by—and aspire to—thinness. Thinness became encoded as a part of the creation of desire, for all sorts of reasons that, if you’re reading this, you probably understand. The thinking here is that

Vogue’s move to not use models who appear to have eating disorders will help separate that encoding; certainly

Vogue will remain a manufacturer of desire, and they have all sorts of talent beyond emaciated models to do so. I’d love to see thinness separated from desire just as much as the next woman. But the

Vogue announcement, on balance, is never going to be a part of that, for on the most basic level, simply refusing to work with models who “appear” to have an eating disorder hardly means the thin imperative will vanish from

Vogue’s pages.

We have encoded acquisitional desire as thinness—you can never be too rich or too thin—and the entire industry is predicated upon acquisitional desire. Yes, yes, magazines should do their part to end the conflation of thinness and desire, and on the most perfunctory level,

Vogue has done so. But the work—the real work—must go far deeper.

For as significant as it is that it’s

Vogue, with all its class and tastemaking connotations, making this announcement, it’s also a double-edged sword.

If the go-to reference for the absurdity of the thin imperative has always been Vogue, and then Vogue says it’s switching up the game, we’ve suddenly lost our reference point. Yet the referent still exists. Models are going to remain far thinner than the average woman, fashion images will continue to do their job of creating longing and desire, and otherwise sensible women will keep doing the master cleanse. All that has changed besides models' labor conditions is that

Vogue gets to seem like it's doing the right thing, and those who have been agitating for body positivity get to feel like we've made progress.

Vogue is doing nothing truly radical to change the thin imperative, and to pretend otherwise is to silently walk in lockstep with the very system that put us in this situation to begin with.

There are other concerns with the announcement as well. Some argue

it doesn’t go far enough, and I’d agree;

certainly not everyone who has an eating disorder "appears" to have one, and when you’re talking about a workforce whose livelihood depends upon skilled manipulation of self-presentation, that risk runs even higher. I’m also a hair suspicious of the timing—both as a PR move to smooth over damage done by

“the Vogue mom,” whose controversial piece in the April issue detailed putting her 7-year-old on a diet, and as a reaction to where

Vogue is positionally. The circulation of American

Vogue dipped 1.7% in the first quarter of 2012 (though it did extraordinarily well in 2011, earning the title of

Ad Age’s magazine of the year), and the slow decline of its readers’ personal income may be figuring into their outlook. From 2008 to 2011, Americans’ average per capita income grew slightly (with some recession dips); in that same period, the

Vogue reader’s median income dropped, from

$64,429 in 2008 (which in and of itself was a 2.3% dip from 2007) to

$63,094 today. This keeps

Vogue readers substantially above the national per capita income, but

I can’t help but wonder if this is an acknowledgment of the behind-the-scenes middlebrowing of the title. For all its prestige and class connotations,

Vogue hasn’t been as highbrow as we might think; when I worked at a teen magazine a few years ago, I was surprised to find that readers’ parents were slightly better off than

Vogue readers.

And let’s not overlook that Conde Nast’s truly highfalutin’ title, W—which has a median reader income of $155,215—has made no such announcement. W has the luxury of doing whatever the hell it wants;

Vogue needs to stay relevant to people outside the inner circle in order to continue its success. I’d like to think that prestige audiences care about body image diversity as much as the average American woman, but I’d be thinking wrong.

Despite my arguments here, I

am pleased that

Vogue is making efforts to stay relevant and on-point with a growing national conversation about body image. I’m critiquing, not criticizing, the announcement. It’s at least a gesture in the right direction—and it’s showing that a critical mass of complaints and activism can actually work, which is enormously encouraging for all the body image and media literacy advocates who work tirelessly in the face of some daunting and culturally embedded issues. And, again, the labor impact here is significant. But as far as its larger impact on readers, I’m not ready to cheer.

Short of a complete and total ideological overhaul, there is nothing Vogue could do to truly change the story, for it’s a business that revolves around creating and sating acquisitional desire; it’s why Gloria Steinem referred to the relationship between advertising and women’s publications as the

“velvet steamroller.” The policy changes won’t hurt women’s body image, I don’t think. Neither will it truly help. As long as

Vogue is a part of the machine of desire—and there is no way for it not to be—the narrative will remain the same; imagery, truth, and beautification will continue their morality play; and readers will receive the same message they always have. And a very thin band will silently play on.