(via)

Nancy Upton and Shannon Skloss knew something not-so-inclusive was going on when American Apparel suddenly decided to create clothes for a larger size range and launched it with a “model search” contest. The Dallas duo was bothered by the pandering language used in the ad (the headline: “Think You Are the Next BIG Thing?”) and also knew that after years of refuting the need to include larger women among their clientele, chances were the company was only reversing its position because it was teetering on the edge of bankrupcy. Upton, a performer, staged a shoot with friend and photographer Skloss in which Upton posed with food: submerged in a bathtub of ranch dressing; holding a cherry pie between her legs; kneeling on hands and knees with an apple in her mouth, suckling-pig-style. And, of course, she won the contest.

Now, once you know that Upton was intending this as a subversion of both American Apparel and our culture’s ideas about fat women (as a size 12 Upton qualifies as “fat” in the eyes of the fashion world), it certainly seems a whole lot cooler than it does when you see it as a straight-up representation of AA. But I have to wonder how subversive something can be when it meets every criteria of the very thing that it’s mocking. The photos are beautifully, suggestively styled (a credit to Skloss); her makeup and hair look fantastic; she’s doing weirdo things just like in any other weirdo fashion shoot. And then the point of the whole thing: Upton is gorging on or surrounded by food in every shot, the idea being that women of size “just can’t stop eating” (Upton’s tagline on the AA contest site).

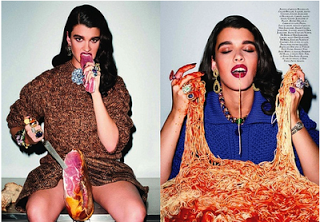

Upton and Skloss’s intent was subversive, but in fact it looks pretty much exactly like a straight-up plus-size photo shoot—specifically, this Crystal Renn shoot in French Vogue, in which she’s dipping her hands into spaghetti and wielding a carving knife over a slab of meat that just happens to be placed at her crotch.

It’s particularly questionable when linked to American Apparel, even if the entire idea is to mock the company. AA’s advertising ethos appears to be non-models who look like they’re exploiting themselves. (Emphasis on “appears to be” and “look like”—the disturbing stories of questionable circumstances surrounding these photo shoots taints all of their ads, not that much more is needed to taint the AA name.) The people in American Apparel ads are store employees, not professional models; they’re shot and presumably doctored in a way that makes them seem like the outcome of a druggy evening during which some dude gets all, “Hey, I’ve got a camera, baby”; and the models are often splayed out in positions even more awkward than your average haute couture shoot.

In short: Upton’s collection resembles what American Apparel might very well do in a plus-size photo shoot if left to their own devices. I’ve no doubt that if Upton had submitted the exact same photos but had sincere, not subversive, intent, her photos would be featured in their advertisements. When I first saw the shots, I recognized the nod to performance art but since it was presumably aimed toward getting a contract with American Apparel, I didn’t consider the notion that it was satire. (Thanks to reader Anna, who pointed me toward Jezebel’s interview with Upton and better informed me on the matter than when I mentioned it in my roundup last week.)

These provocative photos beg questions larger than I’m qualified to tackle: How much does the creator’s intent matter in art? If you have to know the background in order to spot the subversion, can it be effective? If the goal is to raise awareness of an issue and the only people who get the joke are already informed, have you succeeded in your goal?

Upton and Skloss have gotten a good amount of press on this—including broad audience sites like The Daily Beast and Yahoo News, cluing more people into the joke, and perhaps presenting the question in the first place to readers of the general interest publications. (Presumably Jezebel readers are already pretty aware that plus-size women get the short end of the stick.) In interviews Upton is clear-minded, acknowledging both her detractors and supporters with grace, repeatedly insisting that she’s just aiming to be a part of the conversation—and she’s succeeding. (For the record, Upton seems pretty kick-ass, and has made it clear that even if American Apparel does actually approach her to model for them since she did, after all, win the contest, she'll refuse.) But the method being used here too closely mimics the very thing that’s being critiqued. That’s how satire works, but in order for satire to be effective there needs to be an element of the ludicrous. The trouble Upton and Skloss ran into was that both American Apparel and the treatment of plus-size women are both already so ludicrous that nothing they could do could out-outrage their target.