A bit of personal trivia: I adore Wizard of Oz. The movie, yes, of course, but specifically the books, all 16 of them, though the only ones I recall in detail are the first four. L. Frank Baum lived for a while in the town I grew up in—Aberdeen, South Dakota—and was briefly the editor of the local newspaper, where he penned terrifically racist editorials clamoring for the extermination of American Indians. But never mind that right now! He also provided oodles of entertainment for children worldwide! (He was an outspoken advocate of suffragism as well, and in fact when Susan B. Anthony visited Aberdeen she stayed with Baum, and Matilda Gage was his mother-in-law.)

Dorothy fascinated me, of course, with her sage youth quality. At age 4 I would purposefully get lost in K-Mart so that I could then wander to the customer service desk and ask them to announce over the loudspeaker that the mother of Dorothy Whitefield-Madrano should come retrieve her daughter, fully believing that if my name were Dorothy over the K-Mart loudspeaker it would somehow actually become Dorothy. But it’s not Dorothy I’d like to look at today, or Glinda the Good Witch, or the Wicked Witch, or even Ozma, the true ruler of Oz, whom you meet if you stick around the series long enough. They’re all fantastic characters, but as far as beauty goes, there’s one character whose existence cries for a shout-out here.

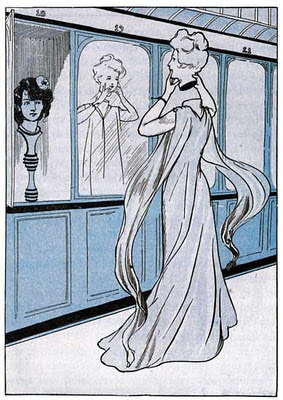

"By the aid of the mirror she put on her head."

So, hey, even a genocidally inclined gentleman recognizes the whole "all types of beauty" thing, so, um, points there, right? But the first thing we know about Princess Langwidere is that she’s so vain that she refuses to seize power, even though the rest of the royal family has been imprisoned. “At present there are at least ten minutes every day that I must devote to affairs of state, and I would like to be able to spend my whole time in admiring my beautiful heads,” she declares. We’re not meant to like Langwidere; we’re meant to see her as a “horrid creature,” even though she gladly cedes power to people who know what they’re doing instead of trying to manage the land herself. (Contrast this to General Jinjur, the leader of the girl army who overtook Oz in a previous book—she’s shown as selfish in her ambition, while Langwidere is selfish in her lack of it.)

I liked her anyway, or perhaps I just envied her. Having not just different hairstyles and outfits, but different heads?! It seemed logical somehow, for isn’t that an exaggerated version of what we’re doing sometimes when we play with makeup? Most of the time I’m trying to just be a more polished version of myself, and I think that’s true of most women—but sometimes I do want to transform, out of sheer curiosity (which some, like Baum, may package as vanity). We dye our hair to see what it’s like to be a redhead; we cut our hair to see what life as a pixie-cut cutie might be like. Princess Langwidere, being fictional, and fictional in a magical land at that, just had advantages the rest of us don’t.

It’s also interesting that Langwidere is drawn as a Gibson girl, the “American girl to all the world,” according to her creator, Charles Gibson. The Oz illustrator was probably just going with the times—the Gibson girl was immensely popular when the book was written, so drawing an image of a beautiful woman meant to draw a Gibson girl. But the Gibson girl was a Langwidere-ish figure herself: Gibson used many models, creating no single, specific icon but rather a multitude of Gibson girls who were understood to be Gibson girls because they fit specific criteria. They were ladylike, young, and spirited, and of course they had that iconic hairstyle, which Princess Langwidere’s preferred head sports in all illustrations of her. They were specific but interchangeable—"logo girls," you might call them—making them perfect both for advertising purposes and for Baum’s mocking of women’s vanity. Is he saying we’re all Langwideres if we preen in front of the mirror and fall prey to new hairstyles? Is he saying ladies with real power—Ozma, for example, or the ever-plucky Dorothy—are above such nonsense?

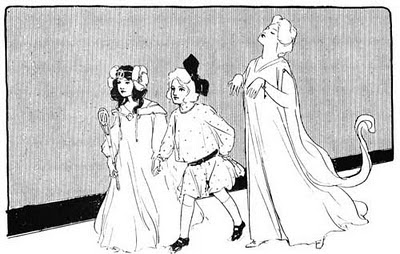

That's Ozma on the left, Dorothy in the middle, and

Princess Langwidere doing an early 20th-century lady gang signal on the right..

Princess Langwidere doing an early 20th-century lady gang signal on the right..

I’m not sure, and I don’t want to read too much into a minor character in a turn-of-the-century children’s book. But I don’t want to dismiss her either. In fictional characters—cartoons, icons, heroines, Muppets—we see women who are literally constructions, and when these characters catch on, it's an opportunity to see what constructions of femininity our culture responds to. What can we learn from the Langwideres, Dorothys, and Glindas about our ideas of femininity? What can we glean from the Betty Boops, the Miss Piggys, the Darias about what we see as ideal in any given era? What fictional characters—specifically characters who haven’t been portrayed by live-action actresses, thus leaving their construction fully in the minds of their creators—have you been fascinated with over time? Do you base your ideas of a character’s beauty on their actions, their words—or, to borrow from Jessica Rabbitt, are they just drawn that way?