A while ago I was talking with a friend about annoying subway behavior. We covered She of the Unending Cell Phone Conversation, He of Legs Spread Wide Encroaching Upon Your Space, and Dude Who Asks What You Are Reading When By Virtue of Reading It Should Be Clear You Do Not Wish To Be Bothered. And then I got to my personal favorite: She Who Applies Makeup.

"I mean, powdering your face, whatever, that's fine," I said. "But putting on a whole face of makeup! I hate that!" My friend paused. "I put on my makeup on the train," she said. "It's dead time on the subway otherwise; I can sleep in a little bit and still show up to work made up if I just do it on the subway." I made some halfhearted attempt to say it was a hygiene or safety issue--that "makeup particles" could fly everywhere (she then pointed out that was most likely to happen with powder, which I'd already given the thumbs-up to) or that I hated having to worry if She Who Applies Makeup would jab her eye out while applying mascara ("That's her problem, not yours," she said).

In theory, I'm all for transparency in government, reporting, and beauty. Preserving the smoke-and-mirrors aspect of beauty upholds the notion that conventional beauty is something accessible only to the chosen few who are lucky enough to be born with clear skin, straight teeth, and balanced or striking features. One of the things I appreciate about the mass beauty industry is the democracy of it: Don't hate me because I'm beautiful; you can be beautiful too. At its best, it levels the playing field (or at least teaches us how to bunt).

So in an effort to be transparent about my beauty routine, I don't pretend like I don't use any of that stuff. My look is rather "natural" (you know, 11-product "natural") so it doesn't scream out that I'm wearing makeup, but neither am I coy about my beauty routine. I use self-tanner! I wear concealer! My eyelashes are not naturally black-tipped, and I did not emerge from the womb smelling like a delicate mix of milk, honey, carnation, and rose.

But when I think of the feeling I get when I see a woman whip out her makeup case and go for it on the subway--an irritability that, if I'm already on edge for whatever reason, can easily tip into something resembling contempt or even anger--I have to admit that I have an investment in preserving a certain beauty mystique. By "beauty mystique" I mean not any particular look or effect, but rather the quality that prompts us to speak of a woman's magic, or her je ne sais quoi, her effortlessness, her aura. Any given woman may, of course, have forms of magic or je ne sais quoi that have naught to do with her appearance, but most of the time we refer to any of those qualities we include the effect of her appearance as a part of the quality we're describing. If we're able to witness the quality's construction, the effect is diminished. And if we witness the construction of any one person's effect--say, a woman putting on bronzer on the subway--we can apply that revealed knowledge to others.

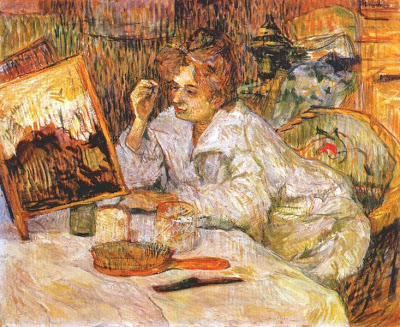

In beauty talk, discussion of the beauty mystique most often comes up in discussion of the irony of how the "natural look" actually requires a zillion products. (Or, in my case, 11.) And that is the clearest example of how hiding one's labor serves to create an air of effortlessness. (Sociologist Erving Goffman in The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life: "In interactions where the individual presents a product to others, he will tend to show them only the end product, and they will be led into judging him on the basis of something that has been finished, polished, and packaged...It will be the long, tedious, lonely labor that will be hidden.") When I'm filled with ire by witnessing a woman putting on makeup in public--doing what I do every day, just in private--I'm taking that idea of hidden labor and turning it into a sort of morality play. What I feel is close to indignance: How dare she let the world know what it takes? Not what it takes to apply makeup, but what it takes to appear feminine in that particular way.

In beauty talk, discussion of the beauty mystique most often comes up in discussion of the irony of how the "natural look" actually requires a zillion products. (Or, in my case, 11.) And that is the clearest example of how hiding one's labor serves to create an air of effortlessness. (Sociologist Erving Goffman in The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life: "In interactions where the individual presents a product to others, he will tend to show them only the end product, and they will be led into judging him on the basis of something that has been finished, polished, and packaged...It will be the long, tedious, lonely labor that will be hidden.") When I'm filled with ire by witnessing a woman putting on makeup in public--doing what I do every day, just in private--I'm taking that idea of hidden labor and turning it into a sort of morality play. What I feel is close to indignance: How dare she let the world know what it takes? Not what it takes to apply makeup, but what it takes to appear feminine in that particular way.

As much as I'd like to think I want that labor exposed, there's a petulant little part of me that wants to preserve that mystique. I don't think women want to preserve that mystique to control other women's access to it (remember, we're not to hate the Pantene hair model, because "you can be beautiful too"), but because preserving that mystique forms an armor against the performance of womanhood being exposed as a shadow-puppet show. "It is a widely held notion that restrictions placed upon contact, the maintenance of social distance, provide a way in which awe can be generated and sustained in the audience--a way...in which the audience can be held in a state of mystification to the performer," writes Goffman. In other words, the more those of us who engage in the performance of femininity reveal to our audience, the less power we have, even if the power in question is a mirage.

As a feminist, I want the performance of femininity deconstructed so we can examine its usefulness, rebuilding it from its scraps so that we can make a new model that's more inclusive, less constrictive, based on our collective wishes and desires rather than the needs of those with the keys to the castle. Transparency equals access; transparency allows us to find common ground. Transparency helps us form sisterhood: It's the very reason that beauty talk can allow for a greater conversation to begin. Transparency can become subversive. And sometimes I want to make sure that beauty stays as opaque, as filled with mystique, as by-invitation-only--the invitation being womanhood, not genes or money--as it currently is. It turns out I'm fiercely protective of the beauty mystique, and I'm trying to figure out why.

Talking to my She Who Applies Makeup friend was revealing, so I'm curious to hear from other women: Do you try to keep your beauty routine private? Is it important to you to be perceived as not putting as much effort into your appearance as you actually do? Have you ever misrepresented your beauty labor--either playing it down, or playing it up (perhaps to demonstrate the importance of an event, as Rosie Molinary discusses here when talking about beauty transparency in Latin culture)?