Gorgeous is beautiful on a mild dose of prescription speed. Gorgeous's eyes are a little wider, the curves a little more pronounced, the skin a little more even, the hair a hint more lustrous. It is more difficult to quibble with gorgeous, with a code still broad enough to let in a variety (though anything but garden-variety) but its fences a bit more structured, perhaps a bit higher. Gorgeous can be cultivated, painted on, but not merely approximated. It's easy enough to approximate pretty, or the bombshell, or hot, but gorgeous? From afar, I wish you luck.

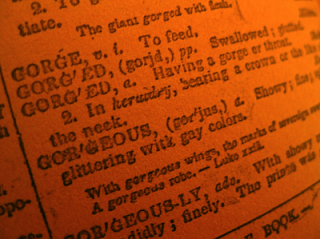

Gorgeous comes from Middle French gorgias for "elegant or fashionable," which likely sprang from Old French gorge for "bosom or throat," and eventually "something adorning the throat," such as throat armor (gorget) or a neckerchief (gorgias). From gorgias, gorgeous arrived in late 15th-century English to mean "splendid or showy."

And from there, the denotation of gorgeous doesn't change much. (Nor does its usage: Since its inception in the 1600s, gorgeous has been used to describe men, women, clothing, landscapes, interiors—anything, really, though we're somewhat less likely to use it to describe men now that royalty is mostly out of the picture.) Webster's currently lists it as "dressed in splendid or vivid colors: resplendently beautiful," or "characterized by brilliance or magnificence of any kind." It's this resplendence that makes gorgeous a word we use more sparingly than beautiful. We may call a woman beautiful because she fits a mainstream ideal, or because of the way she moves or speaks, or simply because we love her. But if we call her gorgeous, we imply that she has a sort technical beauty—and it is a matter of technicality. We use gorgeous to apply to one’s exterior, not her inner riches; after all, the roots of gorgeous are in showiness, adornment, not transcendence. Gorgeous is less forgiving than beautiful: We speak of someone’s acts making them beautiful; whether we mean this on a physical level varies by person, but we don’t speak of someone becoming gorgeous through their kindness. Many people will argue that everyone has something beautiful about their appearance. Few will make that same argument for gorgeous.

To be gorgeous is to be exaggerated in one’s beauty: not necessarily more beautiful, but more alarming in one’s beauty. Perhaps we should be alarmed by the gorgeous, as they apparently make you drop dead (or are prone to dropping dead themselves? The hazard!). The term drop-dead gorgeous entered our vocabulary in the 1960s, and by the 1970s was firmly established—and not only in reference to women, making appearances in Mademoiselle (1976, in reference to leather accessories) and Women’s Wear Daily (1972, in reference to an Italian designer).

Without knowing exactly who coined the term, it’s difficult to say why gorgeous was anointed with the peril of drop dead instead of that honor going to beautiful. (That measure of the hive mind, Google search results, drums up seven times as many results for “drop dead gorgeous” as “drop dead beautiful.”) I’m guessing it’s related to the excess implied with gorgeous that may or may not be there with mere beauty. After all, though the terms evolved separately, both gorgeous and gorge have the same Old French origins—and that word came from the French use of gorge, meaning throat. Gorgeous’s early roots are from a place of heady indulgence, then. Beauty may mean indulgence; it may also mean restraint, a delicacy, a subtlety. Not so for the lavish ways of the gorgeous: I envision a gorgeous brocade covering a gorgeous table supporting a gorgeous stuffed pheasant in a gorgeous room, with gorgeous, gorgeous revelers ready to gorge themselves—all very French, very excessive, and very much taking delight not in merely being aesthetically pleasing, but in being splashily so. The delight of gorgeous lies in its undeniability.

As a coda here: There's another alarming use of gorgeous. In doing the aforementioned Googling, I was disquieted to see find that the word gorgeous is overrepresented when discussing women of specific nationalities—say, French or Chinese women. We fetishize women around the globe: We don’t want a bevy of beautiful Chinese women; we want the Chinese woman (or French woman, or Venezuelan woman, or whatever). If you’re performing a search for “gorgeous Thai women,” you want something more singular than mere beauty; you want something above and beyond.

This might be harmless enough or seem like politically correct quibbling, until you give a search a whirl and find that one of the suggested searches for “gorgeous women” is “gorgeous Russian women,” which leads to gorgeous Ukrainian and Baltic women—that is, women whose economic circumstances and perceived gorgeousness in the United States make them prime candidates for self-export. These arrangements aren’t necessarily abusive or coercive, but I wouldn’t wish upon any woman a husband who found her because he was searching for a splendid show.