For my last haircut, I went to a fancier place than usual, a sleek joint where they bring you herbal tea. The reason for my upgrade was that I wanted to look more professional. Except for my decade of short hair, I’ve had exactly the same haircut since ninth grade: long, gentle layers, some tapering to frame the face, never bangs. It’s a fine, low-maintenance haircut that suits me, but as I approach age 40 I wanted something a little less collegiate. Professional was the exact word I used to the stylist. He proceeded to ask the most logical question possible in this scenario: What is your profession? In other words: What on earth do you mean by wanting to look professional?

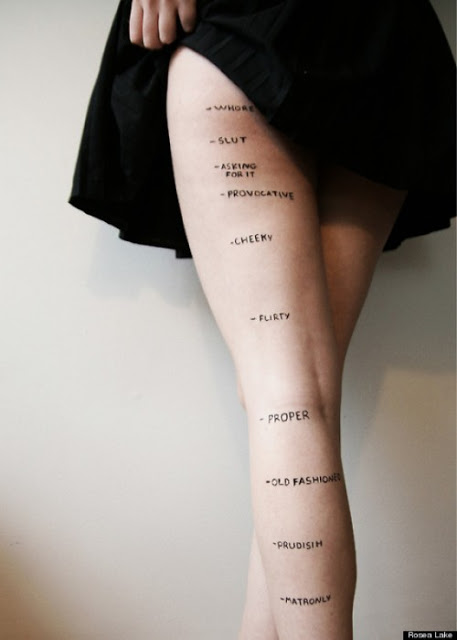

The thing is, I hadn’t taken it further than the word in my mind. I didn’t know how I wanted to look more professional, or how looking professional would translate to my hair. Better? Yes, but in a particular way. More polished somehow, more finished. I kept using these words to tell him what I wanted—polished, finished, professional—and we came up with the cut I wanted. During the cut itself, our small talk deepened, and I told him about my upcoming book. When I mentioned that there was a chapter on the language of beauty—“on the words we use to describe how we look”—he stopped me. "You said you wanted to look professional, and I had no idea what that meant. One person’s professional isn’t going to be another person’s—did you want to look like a news anchor? a stockbroker? a photographer? What does professional mean?"

His questions stuck with me. What I meant by professional was actually polished, something a little more “done” than my usual preferred style. But even that: What does polished mean? That I wanted to look like I spend time styling my hair? Indeed, that might well be it: I’ve stayed freelance for most of my career in part because I love the freedom of being able to work wearing whatever I want, styled only if I choose, a luxury I didn’t have when I had an office job. But I got a fancier cut in an effort to look more like an Author—whatever that might mean—the idea being that if I look less like someone who churns out blog posts crammed in coffeeshop corners and more like someone who writes from a proper office (even if that office is from home, which it is), it might translate into people taking the book just that much more seriously. Looking professional meant, in my head, looking like I didn't have to scramble as hard as I actually do. Looking professional meant looking less like a writer and editor who lives entirely off the “gig economy,” and more like someone with the luxury to style my hair every morning.

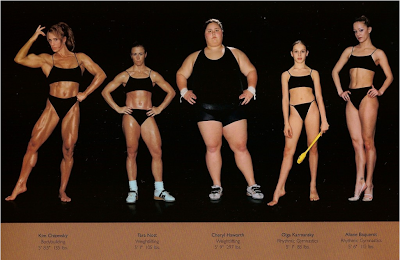

Looking professional means sending a set of signals that amount to looking like one belongs in the professional class: not laborers, but people who can buy expensive styling creams, get frequent trims, and spend time and money to do things like minimize frizz. It means looking like you require the labor of other people to begin with (it all begins with a good cut, right?), and then requires our own unpaid labor to maintain. Looking professional revolves around labor.

I’m reading The Future We Want: Radical Ideas for the New Century, an essay collection from millennial radicals and socialists that serves as a sort of manifesto for an alternative future that would actually serve young Americans, and the rest of us too. My ideology is far too muddled for me to convincingly call myself a socialist (and don’t mistake this post for me feeling the Bern; I feel it just fine, but Hillary 4-eva), but in reading the book, I kept coming back to this: I had assumed that a good haircut would help me look more professional, which, under the rubric I'd lined up, is a good thing. But I'd assumed it was a good thing because we're living under capitalist strictures that assume being a member of the professional class is a goal for the working class. Looking professional would help others see me as a good producer: as someone who knows that spending her time in the production of goods—”creative” goods, sure, but goods nonetheless—is what forms her value in society.

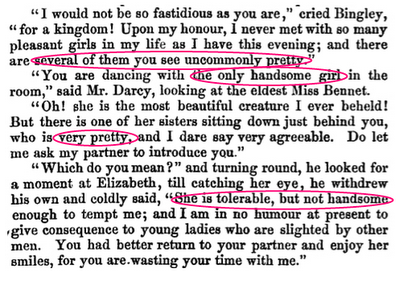

I often mention in an almost offhanded way how beauty is presumed to be so much of a woman’s worth in society, which it is. Looking professional isn’t necessarily about being beautiful per se; it’s a set of signals that can be created or purchased by anyone. It appears to democratize beauty, or at least one form of beauty. But this particular form of self-presentation gets to the root of what socialists might finger as the beauty problem: As long as we tie a woman's looks to her worth, beauty is a good, not a concept, and as long as we live under capitalism, beauty will not be something that can be fully enjoyed or used directly by its creators. As long as we treat beauty as a good, women are not going to be able to enjoy it as fully as we might otherwise—as a place of joy and pleasure. We still do that, for sure. But if you squint, you can see a world where the value part of the beauty equation is removed. And isn’t that lovely?

I’m wondering what other people envision when they think of a “professional” look, for women and men. I’m still picturing a 1980s-style vibe: men in suits, women with helmet hair and shoulder pads, even as I wanted neither helmet hair nor shoulder pads for my own “professional” look. What does professional mean to you when applied to a look? And how does that compare with how you view your profession, or the idea of yourself as a worker or laborer?