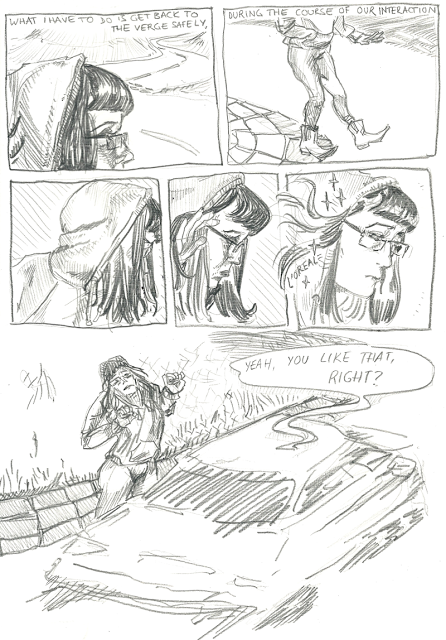

When I was 16, I failed my driver’s license test. The details are fuzzy, but it involved a collision with a curb, and a generous interpretation of LEFT TURN YIELD RIGHT OF WAY TO ONCOMING TRAFFIC. The instructor had me turn back immediately. I didn’t have a chance to parallel park.

I sobbed the entire way home, my mother doing her best to soothe her despondent daughter, who wasn’t having any of it. The minute we got home, I went to my mother’s bathroom cabinet and swallowed two of her antihistamine pills. One was enough to make me fall asleep for hours. Two, then, would do even better. I slept all day, woke up for dinner, took another pill, and slept some more. Failing my driver’s test was, without exaggeration, one of the worst things that had happened to me in my life.

I mention the pills because as childish as taking them was, it seemed like the only way I could handle a truth I discovered for the first time that day:

You can be a smart, level-headed, "good" girl, and you can still fail. I possessed the sort of intelligence that meant while my critical thinking was frequently lazy, tests, papers, and good grades came easily, despite conspicuously infrequent study sessions and lackadaisical homework habits. Failure simply wasn’t on the radar. I’d been disappointed, sure—not getting the lead in school plays, my French class partner not asking me to the winter formal—but I hadn’t

failed before. But there I was, “did not pass” circled on top of my driver’s license application.

Failure is acutely uncomfortable. It’s something we don’t speak freely about, preferring to move on to how to

not fail next time, or perhaps to inspirational quips about how our failures aren’t measures of us as people—which they’re not. We’re so afraid of failure that we turn it into a unique, private sort of shame.

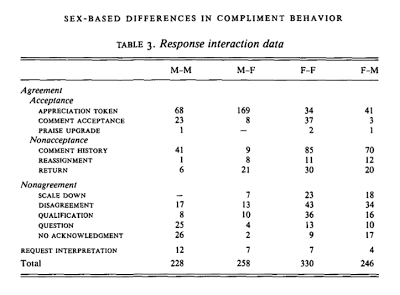

Rather, women are so afraid of failure that we turn it into a unique, private sort of shame. Women fear failure more than men, and we take it harder too:

There’s a strong correlation between academic failure and depression for young women, but not for young men. That’s not to say that men don’t fear failure—of course they do—but the intensity of that fear, the hold it can have over daily life, seems to have a particularly rattling effect upon women.

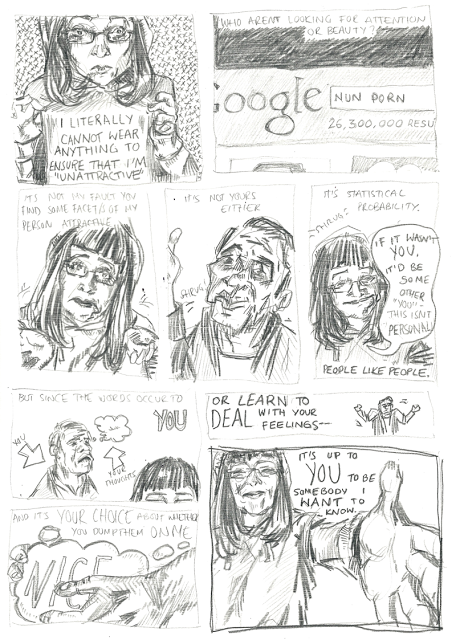

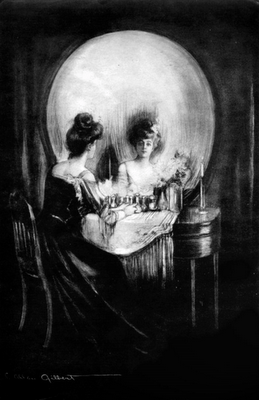

The particular intensity of women’s failure makes me wonder about how we absorb our failures of beauty, which by their nature can’t stay private and include the shame of having others know we’ve failed.

Is there a failure more immediately public than trying to look beautiful and falling short? This is why we ridicule women who make no bones about the fact that they

goddamn well are trying to look beautiful—the “fashion victims” of the world, the plastic surgery cases gone wrong. It’s why the cruelty Todd Solondz inflicts in

Welcome to the Dollhouse is in sharpest relief when Dawn Weiner is trying to look pretty, not when she’s her normal dorky self.

It was the effort-filled image on the left, not

the ordinary dork one on the right, that was selected for the iconic

poster design of Welcome to the Dollhouse.

Our attempts at achieving conventional beauty can actually

become conventional beauty—part of why I know I look “right” (if not babelicious) when I do office work is because I’m neatly dressed and wearing “professional” makeup.

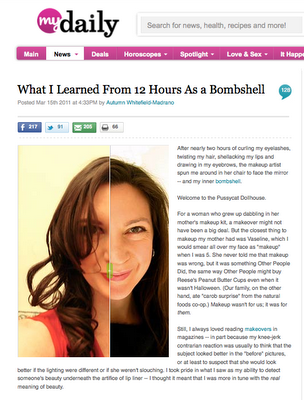

But we also know that attempts at beauty can be seen as a mark of failure, and that if our sleight-of-hand fails, humiliation waits. Witness the

anecdote from Siobhan O’Connor of

No More Dirty Looks after she’d issued a “glam makeup” challenge to her readers: “We had people privately e-mailing us and saying,

I just can’t do it... I guess the mentality was,

Well, if I look bad with no makeup, no big deal. But if you look bad with makeup—it’s like you’ve said to the world,

This is the best I can do.” In other words, we were scared to fail.

I’d like to think that the amorphous nature of beauty makes it something impossible to fail at. Logically it should be impossible to fail at something there’s not a clear standard for. We might not look as good as we’d like sometimes, but to call that

failure seems inaccurate. When I am feeling good about myself, beauty is not something I can fail at.

When I’m feeling less than my fullest self, however, beauty becomes something that not only can be failed, but something I feel I’m destined to fail. In the moments when I’m feeling not “pretty enough” but “never enough,” the efforts of my beauty work seem futile. There is a reason the phrase "lipstick on a pig," which has nothing to do with either lipstick or mammals of any kind, conjures such a potent, damning image.

None of this is to say that women who meet every standard of conventional beauty without particularly trying are exempt from the fear of failure I experience at my lowest. When I think of why I took driver’s exam failure so hard, I now see it wasn’t just because I’d failed, but because I’d mistakenly equated it with other gifts I’d been given. Because I did well in school without ever having to try, I began to believe that my innate, unchangeable intelligence was responsible for every success I had. Like plenty of other bright little kids,

at least according to the Harvard Business Review,

I'd learned to see making effort as a sign that my intelligence had reached its limit. I understood the mechanics of driving, but unlike writing an English paper, I couldn’t get by on my inherent ability. It takes skill, not talent, to learn to naturally keep one’s eyes scanning front, sides, and back, and to learn how traffic works. It would take practice for me to become a good driver. Practice meant effort, and effort meant failure—which, when you’re a bright kid who’s never failed a test in her life, means doom.

Likewise, the effortlessness of the “natural beauty” can be a mixed blessing. Naomi Wolf writes in

The Beauty Myth that women who are genetically blessed with good looks often wrestle with the beauty myth more than average-looking women; they come closer to the societal ideal, so the sting of falling short is forever closer. That’s one way in which “natural beauties” and natural (smarties?) are parallel, but it’s not the only way. I remember a friend of mine who was always “the pretty girl” growing up talking of how she’d flare up with anger whenever someone would tell her how beautiful she was.

“It’s like being complimented on your shoe size,” she said. “I can’t help how I look.” The idea of your value lying not just in your looks but specifically in something you cannot help can short-circuit a woman. It can keep her from daring to fail. Not necessarily at beauty, but at other things we associate with beautiful women: femininity, docility, power, for starters. Not all these things need to be failed at in order to be reckoned with, but they need to be examined in order to be assimilated or rejected. An inability to fail can turn a woman into a different sort of female eunuch.

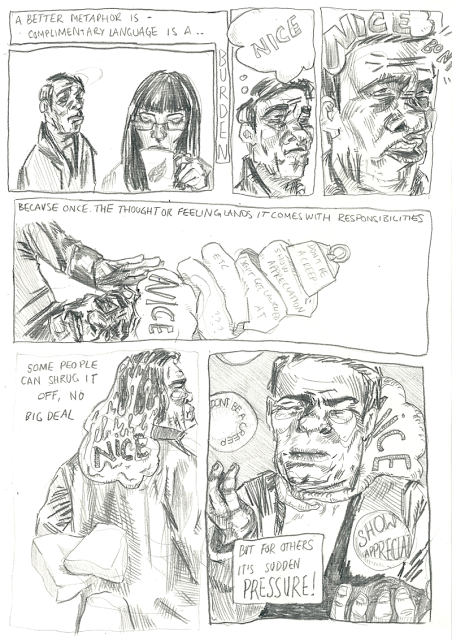

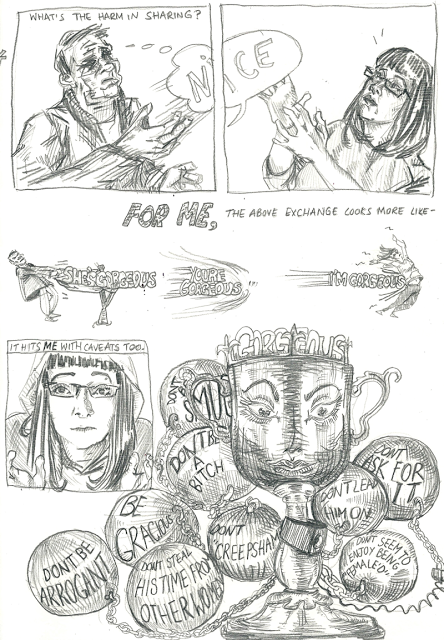

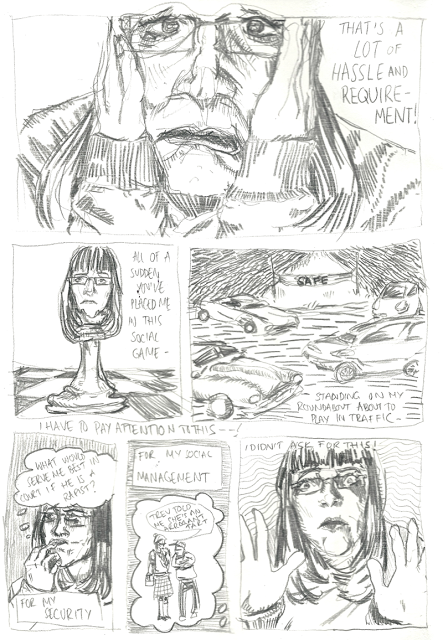

Smart kids can be praised for their effort instead of their natural intelligence to help ensure they’ll actually try at difficult tasks, but carrying over that approach to beauty makes little sense:

Praising the effort of beauty denigrates the praise itself, because the point of much of our beauty work is to hide the effort. I can’t help but feel the slightest bit dissatisfied when my gentleman friend tells me I “look nice” when I’ve dressed up, because it feels like he’s complimenting my efforts—my curled hair, my well-chosen dress—instead of the way I

look. To receive direct praise on those things calls attention to my efforts, leaving me embarrassed for not having been naturally gifted enough in the first place. Yet if all the genetic gifts in the world were mine, I may well suffer a feeling that I have no control over my “giftedness,” and effort might seem even

more shameful. It’s one thing for a 16-year-old girl to melodramatically swallow two allergy pills in order to sleep away the shame of failing her driver’s test. It’s quite another for a woman riddled with insecurities to walk through the world with a mantle of that shame every day of her life.

Our accomplishments—jobs, recognition, awards—are things we achieve.

Beauty, we’re told, is both an achievement and who we are. It’s both our essence and our goal. We live in this awkward space between the effort of beauty and surrendering to nature’s assignment of it; as long as we treat beauty as both the essence of woman and her fundamental goal, its importance will fester in each of us like mold. The contradiction between achieved beauty and natural beauty sneers at us every time we put on a full face of makeup and still feel lacking, and every time we eschew makeup because it wouldn’t matter anyway. It’s damning to the woman for whom conventional beauty is an “achievement,” and it’s damning to the woman for whom it’s a genetic gift.

Living in contradiction is so uncomfortable that it’s become a logical puzzle for philosophers from Aristotle to Nietzsche; Marx believed the contradictions of capitalism (very rich people living alongside the very poor) would eventually become so unbearable that it would eventually collapse, giving way to a revolution. As much as I’d love to see a sort of psychic revolution come to every woman who has struggled with feeling confined by beauty or her perceived lack of it, I’m not sure what that would look like, much less where to begin.

What I suspect is more likely—and, given how many women actively enjoy aspects of beauty work, more desirable—is something less like a revolution and more like what Hegel termed

Aufhebung, or sublation.

The idea of sublation, as I understand it, is that two contradictory ideas can be held in tandem, so that each reflects upon the other. That is, the ideas can coexist without necessarily fighting to the death for their survival.

I’m not entirely sure what the sublation of beauty’s contradictions would look like. Perhaps it’s so familiar that I’m unable to recognize it.

Perhaps every time I sweep up my hair, put on my lipstick, and waltz out the door feeling unassailably together, I’m participating in the sublation of beauty’s contradictions: maneuvering the artifice of beauty to allow my humble version of “natural beauty” shine, regardless of how well I match the template. The achievement aspect of beauty work can, under the right circumstances, unshackle us from the fear that our natural gifts won’t help us make the cut.

There’s another aspect of Hegel’s sublation that I think applies here, and that gives me greater hope. Part of sublation is comfortably existing in contradiction instead of ironing out all opposition, accepting conflicting concepts as forming a truth more genuine than any party line could allow for. There’s no absolute knowledge, because nothing can be true at all times in all situations.

So as painful as the experience of beauty’s contradictions can be, they reveal to us that just as there is no absolute knowledge, there is no absolute beauty. Beauty is not merely in the eye of the beholder, but is subject to changing conditions, to shifting contexts: What is beautiful in one moment may not be beautiful in the next. But our conditions and contexts are ones we can create.

It’s a luxury of beauty, actually—even the most intellectually lacking or gifted students are stuck with whatever conditions the SAT boards create for college entrance exams.

We create our own conditions with our beauty work, with the sleight-of-hand that makes up our morning metamorphosis. We create them with cultivating style, a “look,” a routine that allows us to walk through the world feeling our best. Most important, we create conditions of beauty through those around us: through friends, lovers, images. All of these come together to subvert an absolutist idea of beauty, as unlikely as that can seem in moment of despair. And if we create our own conditions, we prevent our own failure.