What's going on in beauty this week, from head to toe and everything in between.

From Head...

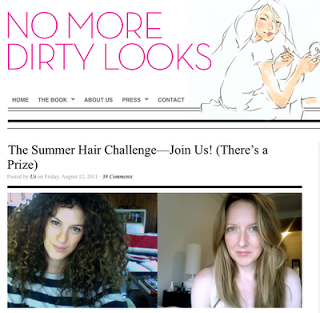

Au naturel: No More Dirty Looks is doing another hair challenge, and it's a good one.

Send in a picture of yourself with your natural hair—no blow-drying, no product beyond shampoo and conditioner (no leave-ins!)—to the green beauty site, and you'll not only help show what the real story is behind "natural hair," you'll also be entered to win a hair-care gifting from NuboNau. Challenge ends Sunday, 8/21, so get a-snappin'!

Year without mirrors, days without makeup: Kjerstin Gruys of Mirror Mirror Off the Wall is upping the game with embarking on

makeup-free Mondays. Check out

her first post on the weekly event.

...To Toe...

Sarah Palin's polka-dotted tootsies: News or not news?

You decide.

...And Everything In Between:

Beautiful Girls: The pilot episode of

Beautiful Girls, a show about employees at a cosmetics company, was

picked up by Fox. This has the potential to be interesting, as it's the work of Elizabeth Craft and Sarah Fain, who collaborated with Joss Whedon on

Dollhouse, which was a thoroughly engrossing look at appearance, identity, the idea of "perfection," and being looked at.

Birchbox biz: Interview with one of the founders of Birchbox, a subscription-based box of curated, personalized beauty product samples sent to you monthly; focuses on the business end of things but still interesting to those of us who aren't so inclined.

Tip of the...nevermind: The department of health in the South African province of KwaZulu-Natal will

start offering circumcision to 10% of the male babies born there, in a reversal of custom (currently circumcisions are only performed for medical or religious reasons). Why? Foreskins are commercially valuable, used in anti-aging treatments (in addition to more legitimate medical uses). As Reason notes: "2.3 million foreskins are at stake." (Okay, that phrasing is ridiculous, but I'm firmly against circumcision and it's upsetting to think that profit could be driving this.)

Natural cosmetics in the Middle East: Sales are

expected to grow 20% this year, but that's only up from 0.01% of the cosmetics market (compared with 3% in North America and Europe). The theory is that the growth in awareness of natural foods trickled down to cosmetics, but since there's no similar drive in the Middle East, the market has to create itself.

Mean stinks: Secret deodorant, in an effort to up its profile à la Old Spice and Axe,

launched an anti-bullying campaign with the "Mean Stinks" tagline. "Secret stands against things that stink, whether it's body odor or mean behavior like girl-to-girl bullying," says a Procter & Gamble spokesperson. It (hopefully!) goes without saying that I'm anti-bullying, and I'm glad to see smart minds like Rachel Simmons of

Odd Girl Out pairing with star power like cast members of

Glee. But...I dunno. The kids who were always teased the worst in my junior high/high school were ones whose home lives were clearly in such disarray that their personal hygiene wasn't a priority for either them or their caretakers. The Secret campaign is anti-bullying, girl-positive, and is not

at all encouraging people to use deodorant to prevent their own bullying. Except...by virtue of it being a deodorant, that

is also sort of an unspoken message. Am I reading too much into this? Yay for anti-bullying, though!?

Heidi Schatz on being "cute": "By golly, I will try on lingerie until I no longer laugh when I see myself in the mirror." (via

Already Pretty)

Guerrilla complimenting: From

Decoding Dress—"Why, of all the women she passed on her way to wherever she was going, did she choose to offer such an

apparently non-violent but utterly confrontational compliment to me?" I'm generally in favor of complimenting other women, and I don't necessarily intend to stop. A friend of mine once astutely

observed, "A well-placed and heartfelt compliment between women can sometimes feel subversive," and it's a point I stand by. Still, Decoding Dress's meditation on the self-indulgence and self-gratification of complimenting adds a new shade to the conversation here.

Woman in the mirror: Advertisers are placing their goods on mirrors, which seems like the missing link between "the commodity of the self" and personal branding that

Marginal Utility laments.

How girls look good: Amusing

piece at Vice on the various products we use to be pretty in "juuuust this other way." (And besides being amusing, it's one of the few places I've seen the socioeconomic dance of salons being discussed.

Beauty Schooled, the conversation is happening!)

Questions for perfect-looking women: I wrestle with the term "perfect," but I know exactly

what Stephanie Georgopulos is getting at here. "Does perfection bore you? Do you look at people like me and wish your hair would frizz a little, that your bra would peek out? Do you ever want to let your nail polish chip? Or is this, the coiffed hair, the ironed shirts; is this your version of happiness?"

Poetry break: "The Beauty Myth," by blogger Shine.

Why don't you wear hi'jab?: Nahida at The Fatal Feminist is sort of tired of the ever-present question among Muslim feminists, but

addresses it eloquently nonetheless. "There will most likely come a day when I will wear hi'jab. ... Maybe just that day, I needed an extra dosage of modesty, because I could feel myself becoming vain. ... Hi'jab means something to me—in relation to my spiritual self, to modesty, and to God.... It is only for me to evaluate. I will be the only one who knows what this means.

"

Flying while fat: Regan Chastain at Dances With Fat offers

much more reasonable options than, say, shame and humiliation for larger air passengers. (The usual "well THAT oughta solve it!" answer is to have fat flyers purchase two airline seats, but as Regan points out, that isn't as easy as it sounds.)

Blogosphere body love: There's always a lot of great stuff going on in the self-acceptance sphere of the Internet, but this week seemed particularly awesome. Tori at Anytime Yoga puts it as plain and simple as you can, with

"I don't want to change my body"; Courtney at Those Graces

lets go of pretty; and Virginia at Beauty Schooled reminds us that "cleavage wrinkles"

are not a thing.

"Life's a banquet and most poor suckers are starving to death!"

News flash, you don't shrivel past 55: Speaking of "a thing," I'm questioning the pulse over at Allure, which

declares that "Granny Beauty" is "officially a thing." I know they're trying to acknowledge the superlative style age can bring, but making style awareness of senior citizens a "thing" seems a tad degrading to me. Auntie Mame, my fashion-plate 85-year-old grandmother, and any of the subjects on

Advanced Style would probably be surprised to learn that the wisdom they've acquired over the years—plus the financial means, confidence, and fuck-it attitude that comes with age and that helps one become a style icon—is a "thing." Yay for recognizing the fashion sense of people of a certain age; boo for indicating that it's a trend as easily discarded as jeggings.

The health/beauty conundrum: Virginia

gets to the heart of one of my major concerns: Is "health" sometimes a convenient cover-up for beauty concerns? "I’ve noticed that those who reject that plastic beauty ideal in favor of 'natural beauty' are often nevertheless still saying that health and beauty are one and the same. They just get their 'healthy glow' from vegetables and yoga instead of tanning booths. Of course I see why that’s better—but I’m still worried about making health and beauty synonymous."

Assume positive intent: Sally asks what would happen if we assumed that those clunky comments we sometimes hear about our appearance came with positive intent. It's an interesting question, because appearance is both a way we connect with others in an immediate sense ("Cute shoes!" "Thanks, and I love your dress!"–that can be an entré, and a manner of appreciation), and a well of attachments we can use to undermine others and ourselves (as in Sally's example, when an acquaintance told her she'd look so much prettier if she'd "just put on some makeup and a skirt once in a while"). Where do we draw the line between setting others straight on appropriacy of their comments and assuming positive intent? I don't think I've found an answer yet. You?