See, the minute you have the word beauty in your blog’s metadata, the Marketing Powers That Be descend upon you with offers of free samples for your review. Lotions, polishes, tonics, scrubs, glosses, serums, creams—if it’s in a bottle and designed to perform miracles, its press release may find its way to my inbox.

The first time I received an offer for some review samples, maybe four months into my blogging venture, my knee-jerk reaction was hell no. Through my years in ladymags, I’d become cynical not only of the “advertorial” function of beauty pages, but of the products themselves. The first few times you see an entire bin filled with fifty-plus types of blush, it’s exciting, but after a bit you begin to realize that it’s all just packaged petroleums and tints and talcs, and that the item you’d been paying $8.99 (or $26, or $56) for is actually just worth pennies, and that for the most part there isn’t really that much difference between the products. (The number-one question beauty editors are asked is, “But what really works?” Yes, there are some that do, but that’s another post.)

So the lure of free products didn’t hold much sway over me; I still have a handful of unopened products from various beauty sales over the years. More important, I prided myself on not falling into the advertorial trap: No, I was not going to give companies free advertising—that is, my time and labor—in exchange for a prettily packaged batch of titanium dioxide. There’s absolutely nothing wrong with doing that, but A) there are plenty of product review blogs already, and I have nothing to add to the chorus except SEO bumps for the companies; B) that’s not what this blog is about, and in fact when trying to explain what I do here, the first words out of my mouth are usually something like, “It’s a beauty blog, but not, like, lipstick reviews”; and C) after years of working in ladymags, I’ll be damned if my passion project—for which I receive the occasional stipend from my syndication with The New Inquiry but which otherwise isn’t monetized in any way—was under the sway of anything other than my editorial judgment. I decided long ago to not have advertising or sponsors for this reason—even from companies and organizations I think do good work.

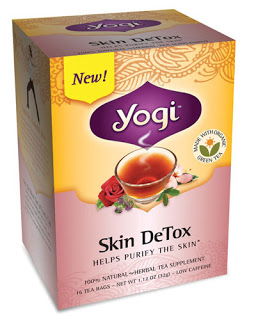

Yet the product offers keep coming. Sometimes, in the case of particularly hilarious-sounding products, I’ll fantastize about accepting and then ripping the product to shreds. But honestly, I don’t get my jollies from thinking of clever quips about silly products—and since my reader base is healthy but not enormous, I’m being targeted by a lot of startups and beginner companies, and I have little interest in mocking them. (Plus, I think most companies subscribe to the “no such thing as bad publicity” line of thinking. I mean, have they read a single entry of mine? I’m more likely to write a 2,400-word screed on “the secret language of toner” or some shit than I am to just be like, “Pores smaller!”)

And then came the spray tan.

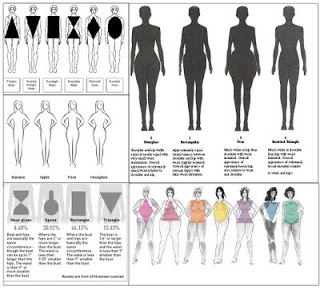

See, I was a sun-shunner for my entire adult life, until a trip to the tropics in 2009 turned me into a full-fledged worshipper. I discovered that not only was it easy for me to develop a light tan, but that I liked how I looked with a tan; once my natural color faded I spent a small fortune on self-tanning lotion. This year I developed a sensitivity to the formula (it makes me itch most unbecomingly); around the same time, I adopted a semi-nihilist attitude that made me realize I had little interest in living past age 80 or so, and decided to hell with it, I’m going to get as much sun as I can, skin cancer risk be damned. (Lecture me all you want; I’ll readily admit you’re right, and will continue to wear SPF 4 regardless.)

Accordingly, I had a tanned summer—but now that beach time has faded, so has my color, and I’m not quite ready to give it up. I knew about airbrush tanning, but am way too frugal to spend the $60 to $90 it takes to get one—plus, the thought of paying a stranger to essentially spray-paint my body brown seemed...I mean, when you think about it, it’s uncomfortably close to those “believe it or not” historical tidbits, like how Romans were supposedly bulimic with their vomitoriums. (Which, by the way, they weren't.)

So when the invitation to “meet Kelly and get a B. Bronz Sunless Tanning Treatment” showed up in my inbox (something to do with Fashion Week?), I deleted it at first, as I do all such invitations and offers, no matter how much the product promises to “dazzle” my readers. But it stuck in my mind. I found myself getting sort of huffy over my own policies, like, Hey, why shouldn’t I be getting the occasional swag? I work hard! Harder than I did in magazines, when I could buddy up to the beauty editors and waltz out of the closet with a lifetime supply of conditioner! You know who pays this blogger's salary? Me! And I’m cheap! And I abuse my staff! And if I weren’t such a rotten boss I might have gone to the beach even more this summer and might have a deeper tan and I wouldn’t even need this body spray-paint thing in the first place, so take that!

I said yes.

I did my homework beforehand; I knew you were supposed to exfoliate and not use any body products so that the tanning agent would be able to better sink in. I also knew you weren’t supposed to sweat for 8 to 12 hours afterward, which might be fine if one’s body is spray-painted in the Helsinki twilight but is more difficult in the recent spate of 90% humidity we subtropical New Yorkers sweat our way through.

I showed up at the spa that was hosting the event and was ushered into the treatment room, where I did indeed meet Kelly, a polished, gracious woman in flowing jersey who looked far less...fake?...than I’d expected from someone who paints people brown for her trade. Actually, as it turns out, Kelly is both artist and chemist: She created the B. Bronz line, which is available both for professional and home use and, from what I saw on the bottles, comes in fragrances like “Citrus Mojito,” which surely is far more appealing than the lingering scent of yo, you just dyed your body brown that I’m all too familiar with from my usual sunless lotion, which shall remain nameless (see paragraph 5). Kelly has the distinction of having tanned members of the National Bodybuilding Association, the San Francisco 49ers Gold Rush Cheerleaders, and the Oregon Ducks Cheerleaders (my alma mater! also, it is impossible to get a natural tan in Eugene, Oregon), as well as Miss Washington, Miss Oregon, Miss Michigan, and Miss California. If I was going to have someone spray-paint my body, I may as well go to the best.

At her behest, I stepped into what resembled a lightweight tent and undressed while Kelly finished spray-painting another blogger’s body. Upon her return, Kelly directed me into various positions—to the right, to the left, leg extended to spray the inner thigh, arms lifted to get my ribcage—while she answered my handful of measly questions that I’d hoped would mask the fact that I’m not really a “beauty writer” at all but rather a cynic who might refer to airbrush tanning as having your body spray-painted brown. Kelly appeased me there too: When I asked about the function of the bronzer as opposed to the actual tanning agent that would keep me golden for about four days, she candidly replied that the bronzer was in the formula “so that the customer feels like she’s paid for something.” Without the bronzer, clients would leave no darker than when they entered, since the tanning agent takes 8 to 12 hours to fully develop. (There’s also a clear, bronzer-less formula available for clients whose supreme faith in the art of the spray tan means that they don’t need to feel like they stood naked in a tent while a stranger hosed them down with brown dye for no immediate effect.)

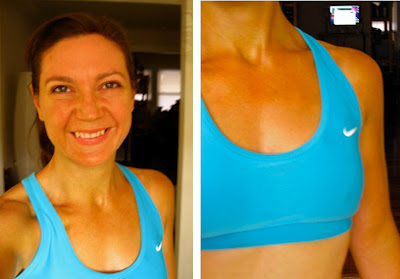

I’d been trying to look Kelly in the eye to telegraph how terrifically secure I was standing almost entirely naked in front of a stranger, but at a certain point I looked down at my arm and saw that it was a gorgeous golden hue, more glowing and vibrant than how I look when I’ve actually been sunbathing. “It’s gorgeous!” I exclaimed, and I meant it, and Kelly smiled before she frowned and started dabbing my cleavage with a towel. “You’re sweating a little,” she said, “so this was getting...funky.” I looked down and saw that my chest looked like someone had splattered coffee across it, brown beads dripping between my breasts.

I stood there trying very very hard not to sweat, while my body dried off for a couple of minutes until Kelly gave me her blessing to get dressed. Which was nice, except then I’d have to exit the cool spa and enter the world of 90% humidity, which I feared meant my entire body would soon look the way my cleavage did. In the subway—possibly the most humid place in New York City save the Tenth Street Russian & Turkish Baths—I stood in the darkest place possible while fanning myself with B. Bronz literature and rubbing my face with a tissue in hopes of at least evening out the sweaty brown beads of body dye that were surely forming there. I studiously avoided eye contact once on the train, hoping to avoid the humiliation of others witnessing me turning into a live Jackson Pollock painting—good thing, too, because when I got up I saw that I’d left a trail of brown drops across the back of the seat.

Having lost all dignity, I made a beeline for home and raced to the mirror, where it turned out that it was only my back and chest that had become mottled (and which was easily taken care of by rubbing in the solution). The rest of me, including my face, had a soft tan glow. Throughout the day, the tone became richer and deeper—though when I took a shower after the prescribed length of time and rinsed off the bronzer, I was left with a golden hue closer to what I’d first seen when Kelly sprayed me in the tent. It lasted for about four days; I can still faintly see the “tan” lines from where my underwear was but it’s barely noticeable.

All this, really, is to say: Thank you, B. Bronz, for the free airbrush tan, which was perfectly nice. And thank you, readers, for allowing me a forum where I can write about beauty without feeling like I need to write about airbrush tans, even the perfectly nice ones—because in attempting to write about it today I find that I don’t know how to do so without swallowing my voice. Which is the opposite of the reason I write here.