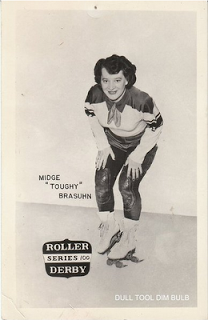

An early editorial meeting at Beheld HQ.

As a feminist who started my career at

Ms. and wound my way through

Glamour and

Playboy before winding up at

CosmoGIRL!—the exclamation point was part of the name—finding Jezebel shortly after its 2007 launch was delicious. I enjoyed it as a reader, and I enjoyed it even more as a worker in the industry they frequently critiqued, especially as I learned that some of their writers had been in my position—simultaneously excited and dismayed to be in the “pink ghetto,” eager to up the feminist content in glossy ladymags but frustrated by the conditions that Gloria Steinem labeled a “velvet steamroller.”

So it’s not surprising that I’m more kindly disposed to ladyblogs than

n+1’s Molly Fischer appears to be. I was 30 when Jezebel launched, and was still eager for what blogs of any sort provided; Fischer, at 20, had gone through adolescence with public critique a click away. I’ve also contributed to two of the four sites Fischer critiques—Jezebel and The Hairpin—and my work there has brought me a portion of The Beheld’s readership, undoubtedly coloring my attitude toward them. I cannot pretend impartiality.

Given the impossibility of impartiality, I admit to being both excited by and uneasy about the

n+1 piece. The whole article is worth a read, but in a nutshell, she looks at the evolution of ladyblogs, sites that give traditional women’s topics signature treatment. (

Seventeen assures you that masturbating is totally normal; Rookie

tells you how to do it.) The bigger the sites get, the more they adhere to what Fischer frames as a particular form of triteness endemic to ladyblogs, in which Zooey Deschanel is shunned but eco-friendly cat bonnets are squeal-worthy. Drained of the gravitas of other alternative women’s media, like explicitly feminist spaces, the potential for ladyblogs to become a true alternative to women’s glossies becomes watered down; the tool for revolution is rendered in scratch-n-sniff.

“The internet, it turned out, was a place to make people like you: the world’s biggest slumber party, and the best place to trade tokens of slumber party intimacy—makeup tips, girl crushes, endless inside jokes,” Fischer writes. “The notion that women might share some fundamental experience and interests, a notion on which women’s websites would seem to depend—'sisterhood,' let’s call it—has curdled into BFF-ship.”

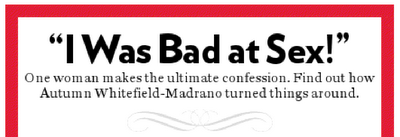

What this argument overlooks is that

a slumber party is sisterhood. Junior high slumber parties might have brought anything from makeovers to pained sobs over family dysfunction to raging tear-downs of pervy gym teachers. The adult slumber party touches on these, with our adult wisdom added to the mix. The voices of women online have brought me my birth control (“Ask Me About My Mirena!”),

lessened my shame about my belly bulge,

shined an uncomfortable light on the way social and personal notions of beauty can collide, and opened my mind to what I, as a biological woman, can learn about my own position in society

from trans women. There’s fluff, of course (

“Watch Kristen Bell Adorably Lose Her Shit Over a Sloth”), but just as silliness coexists alongside our more meaningful concerns, fluffy pieces can comfortably coexist alongside

essays on healing from sexual assault. (In fact, for some of us,

the fluff was a way to heal.) The slumber party goes all night, after all.

By talking about issues particular to women and treating them as though they matter, we create sisterhood. Ladyblogs do that in tones earnest, flip, and everywhere in between; the

“Women Laughing Alone With Salad” Hairpin post Fischer mentions is downright effervescent, and it went viral because it brilliantly encapsulated the way women are painted into a corner where if we’re happy to be eating, it must be because we’re being guilt-free. The post caught on because we all

got it, and because we were all fed up with it too.

Women laughing alone with salad was, in its own way, sisterhood, and to dismiss it as mere quirk is to dismiss the day-to-day stuff that makes up the particulars of a woman’s life. Fischer ends her piece with a rallying cry for sites that stem from “the notion that women might share some fundamental experience and interests,” but I’m not convinced that the sites in question aren’t doing exactly that. They’re doing them in a more lightweight fashion than Fischer might desire, but

the things that constitute gravitas (formality, for example) are frequently structures that purposefully omit the validity of the personal, that look to an “objective” viewpoint (as if there is any such thing) as the end-all, be-all. That is, they’re structures that dismiss the ways plenty of women have written for centuries. Here it comes, that clichéd rallying cry we feminists say over and over: The personal is political.

So it’s unclear what Fischer wants the reader to do—what, when I worked in women’s glossy magazines, we called “the takeaway.” Are we to eschew The Hairpin in favor of today’s equivalent of

The Bimonthly Period, the newsletter of the women’s resource center Fischer’s mother founded during her college years? Sites like Feministing, Pandagon, and Feministe play a crucial role in feminism, and therefore in women’s lives—even for women who have never heard of these sites, as they keep the activist fires burning. They can also occasionally feel alienating. I greatly enjoyed

my guest blogging stint at Feministe last summer, but I also walked away from it understanding, for the first time, why some people whose politics roughly parallel mine refuse to call themselves feminists. For every commenter who thoughtfully critiqued my message, there would be one who’d say I was a tool of the patriarchy, and another who’d accuse me of abusing my class privilege. It’s a vibrant, razor-sharp community and I was honored to be a part of it, but my point is,

if explicitly feminist blogs are the only acceptable online outlet for feminists to inhabit, we’d get exhausted mighty quick. (Let’s also not forget that the number of people who wouldn’t label the targets of Fischer’s critiques as forthrightly feminist is pretty small. The other day I mentioned to a new friend that a mutual writer acquaintance was a “radical feminist”—as in, menstrual art—and her response was, “Oh, does she write for Jezebel?”)

Fischer hits plenty of nails on the head (you know,

my opinions being the bed of nails), especially her questioning of the age-appropriacy of ladyblogs' tone. I enjoy Rookie, helmed by 15-year-old Tavi Gevinson—

in fact, I enjoy Rookie so much at age 35 that I began to wonder how many teenagers actually read it. I’ll happily cheer unabashed femininity, but like Fischer I’m wary of mass numbers of adult women inhabiting teen spaces. In fact, many of my feelings on this topic can be neatly summed up by an excellent Julie Klausner piece that—oops!—

ran in Jezebel.

Still, despite finding aspects of adult-girl culture downright creepy (Hello Kitty?), I see other aspects as liberating. Where women’s magazines place readers on a trajectory of traditional womanhood—teenager to single woman to mommy to retiree—ladyblogs generally treat their readers as though they’re child-free adult women.

Ladyblogs don’t mommy-track their readers—and that’s part of why “lady” makes so much sense in describing them. Classically speaking, ladies were put into a somewhat separate class. Ladies of recent centuries had social status; earlier, they had feudal privileges. The ladyblogs don’t use

lady in that sense, but it carries a separatist air: We needn’t be quite as serious as we might when using the broader term

women, but we don’t want to be

girls. Fischer asserts that “On the ladyblogs, adult womanhood is a source of discomfort, and so when we write posts or comments, we tend to call ourselves ladies.” I’d argue the opposite:

On the ladyblogs, adult womanhood is a given, and within our shared womanhood we carve out a comfortable space we can all inhabit. Within ladyblogs, we all become ladies.

The lingo may be why the presumably adult women on the ladyblogs (Rookie excluded, as it is aimed at teenagers) might seem to be clinging to girlhood. Fischer questions both the hallmarks of ladyblog style and the way its commenters pick up on it. In my own writing I rilly rilly try to avoid the clichés of the ladysphere (amirite, ladies?), because I don’t want to rely on those methods to convey my point. But

as Emily Gould points out, it’s not like “commenter sycophancy” is particular to the ladyblogs. Still, it’s particularly easy to slip into ladysphere lingo, for the very reasons these clichés evolved in the first place:

When skillfully employed, ladymags’ “endemic verbal tics” connote personality. Instead of the self-seriousness of magazines, ladylingo gives a tilt to the voice, one that implies we’re all in it together (which, again, is why it’s contagious). The tics serve as a friendly politesse, a way of conveying that you’re typing with a smile.

In fact, that seems to be Fischer’s larger point, and one I’m ambivalent on: Ladybloggers and their commenters are typing with a smile. “They bake pies with low-hanging fruit: they are helpful, agreeable, relatable, and above all likable,” Fischer writes.

“Surely one can’t, and shouldn’t, strive to like and be liked all the time. But how else can one be?” (I couldn’t help but wonder how much time Fischer spent actually wading around in comments sections. The culture of “like” looms large, but ladyblog commenters can get vicious, and they’re certainly not afraid to disagree.) The point is an excellent one, but two key points give me pause. First:

What’s so wrong about wanting to be liked? I want to be liked; I want my writing to be liked. When I started The Beheld I repeatedly said that all I wanted was to be a part of the conversation. Some writers become a part of the conversation by being controversial, but that’s not my style. I’m a good girl from birth, and it’s built into me to want to be liked. But being liked isn’t my goal in writing; likability is a tool I use to pave my way toward the larger goal of being a part of the conversation, and occasionally hosting it too. There’s plenty to critique about women having a compulsive need to be liked, and it’s something I’ve wrestled with a good deal on a personal level. But

I’m not going to apologize for couching arguments in a softer way than I would if my goal were to win.

But the larger issue here about likability is this:

Maybe if more women writers were published in gender-neutral publications, writing stories that treat “women’s issues” as people issues, we wouldn’t be paranoid about being so fucking likable. This is a much deeper issue than I’m able to address here, and since most of my bylines have been in explicitly female-oriented spaces, I’m not particularly credible on this front. What I’ll say is that I’m not alone in being a female writer who writes about women’s issues who would be happy to publish in more gender-neutral spaces—and that I rarely pitch those spaces because there’s still a little voice inside me telling me that what I write about is just girl stuff. And people, this is what I do, every day: I write about girl stuff, and I treat it with the gravitas it has in my own life. But that voice is still there, and it’s a result of all sorts of things—internalized oppression, the realities of the “pink ghetto” of women’s issues, fear that if I did start writing more for gender-neutral outlets I’d have to face harsher criticisms than I usually do (the only time I’ve been forthrightly called stupid is from self-identified male commenters, and never on ladyblogs). It’s also a result of me specifically wanting to write for women; as they say, I “write what I know,” and what I know is being a woman. And I don’t particularly want it to be any other way; like I said, I’ve written for ladyblogs, and I wouldn’t bristle at The Beheld being categorized as such. Obviously I believe in what ladyblogs do. But I’m a fool if I think there are no other reasons I align myself with them—reasons that have to do with the “belonging” Fischer criticizes in her piece (“[Ladyblogs] tell us less about how to be than about how to belong”). I know I “belong” in ladyblogs, for I am a lady. I’m not so sure where else I belong.

Despite my misgivings, I liked Fischer’s piece. I like the questions it asks, and I just like that it exists. Recent discussions about

women writers and

where our bylines ought to be need to continue, and they can’t continue in an authentic manner if we’re afraid of critiquing one another.

Ladyblogs aren’t above reproach or critique, and given that some of them serve as watchdogs to traditional women’s media, if we become lax in watching the watchdogs we’re perpetuating the problem. I just don’t want the conversation to be a ping-pong of should we or shouldn’t we, of ladyblogs versus the rest of the Internet. I want the sentiment behind Fischer’s piece to be explored so that whatever these spaces look like in five years, they’re serving women’s needs even more.

Perhaps it’s the women’s magazine veteran in me, but I want a “takeaway” from Fischer’s piece, and I want it to be something like this:

We’re in an interesting time as far as gender and access to the public, and we’re also at an time when “voice” is a prime asset for online visibility—“voice” being something women writers have traditionally been told they excel at. We’re also living in a time of fragmented, personally curated information streams, one in which a person could read a handful of sites—even ladyblogs, depending on the blog—and have a reasonable handle on what’s going on in the world. So we’re at the era, and if the proliferation of ladyblogs is any indication, we’ve got the talent. Now what are we going to do with it?

___________________________________________________________

On a related note: I’m thrilled to announce that starting February 6, The Beheld will be syndicated at The New Inquiry. I’ll write more in-depth about this tomorrow but given the topic of this post I thought it would be downright dishonest to not share this bit of news, since TNI is a gender-neutral space that looks at my ladybloggin’ background as an asset, not a ghettoizing detraction. But more on that tomorrow!