"The camera served Tereza as both a mechanical eye through which to observe Tomás's mistress, and a veil by which to conceal her face from her." —The Unbearable Lightness of Being, Milan Kundera (film, 1998)

What struck me upon seeing her sitting at a corner table was her beauty: wide-set eyes, honey-colored curls, creamy complexion. I’d met her once before, so it wasn’t that I was only then seeing what she looked like, but rather that I was seeing her in relation to myself. In my mind there was an algorithm of attraction whose full components were a mystery to me; I just knew that two parts of it were her appeal, and my own. Sitting face-to-face with another part of the messy equation made me question the math I’d come up with: I’d talked myself into believing I’d overestimated her allure the first time we’d met, for if she were really as pretty, charming, and vivacious as I remembered, what was her boyfriend doing kissing me? At the time I was inexperienced enough to believe that the fellow had betrayed her because of some magnetic pull between us, instead of what I now see was the case: He was bored, and I was willing.

“I know it’s weird,” she said, trying to explain why she’d called. “My friends were like, Why do you want to meet up with her? But—” She looked up, her face flushing for the first time since she’d seen me walk through the door. “You understand why I wanted to, don’t you?”

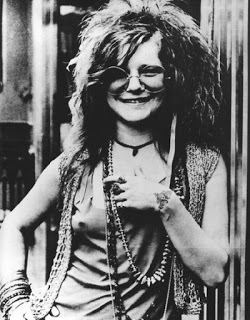

I did. At least I believed—and believe—I did. She had an algorithm to question too. For as I watched her eyes occasionally brim with tears, her head bow and bob with a mixture of sadness and defiant optimism, I began to understand exactly how off my math had been. Despite a bearing I interpreted as confidence, she might have had an algorithm with the naivete of mine: Maybe he went for her because she’s just all that. I saw in front of me someone beautiful, earthy and ethereal in equal measures, capable and grounded, and the thought that she might be questioning her own appeal burned. I wanted her to see herself as I saw her, and it occurred to me that if she was doubting her allure, she might be doing so because I helped her doubt it.

As neutrally as I could, I answered her questions, which began as you’d expect but eventually moved into the territory of a first date. Where are you from, what did you study? Who are you? Easier than you might believe, our conversation began to flow. We both made jokes that probably weren’t very funny, but we were both easy laughs so it didn’t matter. We stayed long after we’d finished our cones, long enough to get sodas because we got so thirsty. At one point she said, “I’m actually having a better time with you than I did on my first date with him.” “Me too,” I replied. It was the truth. We lived in the same neighborhood, so we walked home together. When we parted, we hugged.

Four days later, I saw her again, as I was walking down the street hand-in-hand with her ex-boyfriend. As we passed her, I could see that her steely expression belied a map of tears. He and I broke up a month later. I heard through friends that he tried to get back together with her, but she refused him, just as she refused me when I tried to contact her a few weeks after our ice-cream outing.

I have been the other woman. I could chalk up my indiscretions of this sort to youthful impudence or an “exploration” of sexual ethics or falling for the same old lines, but the truth is I was just plain selfish. Would it help if I tell you that it is a selfishness I have outgrown? Today fidelity is more appealing to me from every angle than its opposite, or even its shyster cousins—inappropriate emotional investment, Olympian flirting. But that is now, not then, when I’d mentally say I was sorry and mean it, just not enough to stop.

What strikes me now about this weakness is not the way I felt toward the men involved, but toward the women. The spritely live-in girlfriend of a man I longed for and did not resist when he told me he shared my longing; the sloe-eyed designer whose partner told me had lost interest in sex with him years ago (of course!); the husky-voiced business major whose date slipped me a note at a party saying he wished he were there with me instead: These women intrigued me, and not competitively so. It would be easy to chalk this up to my own tendency to cast a golden light of admiration onto women in general. It would also be easy to chalk this up to being the other woman, not the—woman-woman? The girlfriend, the partner. The beloved, supposedly. When I tried to explain my bizarre reverence to a friend, she rolled her eyes. Of course you get to feel that way, she said. You won.

I’m resistant to attribute this sensation to “winning,” though, even under the faulty logic of other-womanness as winning, for it's happened when I’ve been the betrayed one too. I once discovered a stash of messages sent to my then-partner by a woman whose name I didn’t recognize, but who clearly knew who I was. Most of the content was your typical affair nonsense, but this was a woman who was thoughtful about me in the same sincere, curious, and egregiously self-involved manner that I’d had in past liaisons.

She’s prettier than I imagined, one of her messages went. My first thought was to wonder what she’d imagined me to look like, and whether my boyfriend had given her clues: She’s medium build/she’s brunette/she’s gotten thick in the waist. But her note continued: It makes me insecure. The admission had the effect of both a stab and a caress. A stab because as much as I hated the existence of this woman, I hated that she too used other women as mirrors that reflected back her doubts. I’d have preferred that she be superhuman, for then I’d have a receptacle for my vitriol that might have allowed me to stay with my boyfriend, whom I loved. And a caress because reading that she shared my own reaction—insecurity, shaky doubt, a plea for affirmation—did allow me to use her as a mirror, did let me see that whatever the reasons for his betrayal, it wasn’t because I wasn’t enough. If she was made insecure by my looks, and I by hers, that canceled each other out, right?, so the reason for the betrayal logically had to be something else. (Because logic and love go hand-in-hand so often, I know, I know.)

In tales of infidelity, we overlook a central fact: Two people share another. She and I already had two things in common—the man himself, and being the kind of women who would pique his interest. In another time, another place, another life, our begrudging sisterhood could have been sisterwives. We would live together, create a home together, prepare food together. I might braid her hair. And secretly, each of us would worry that the other would forever be more alluring to him, therefore—in my grief-stricken, abjectly depressed reasoning of the time—more alluring to all men, everywhere. How could I not be fascinated by her? I looked her up. She was beautiful.

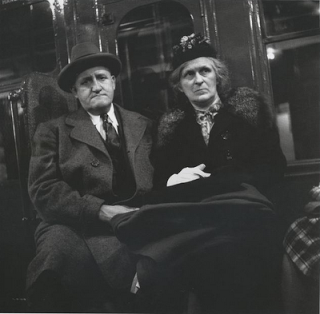

There’s a particular way that someone you become intimately involved with knows you: They know a side of you that remains hidden to not only the public eye, but most private eyes as well. My best friend may know me better than most of my lovers have, but she’s never felt me grasp for her touch in the middle of the night, or seen me through the shaky moments that come after an act of, quite literally, naked vulnerability. What that means is that there are dozens of women roaming around who know those same things about the men who have entered my heart. Ex-girlfriends, ex-wives, yes, and I’ve been fascinated with them as well. But it is the other woman—the woman who knows not the man at age 19 or 27 or 38 or whatever age he has long passed, but the person he is now, the person who may have had dinner with you mere hours after a kiss good-bye with her—that you are actually sharing a person’s affection and attention with, in real time.

That’s what makes betrayal sear so acutely, of course. It’s also what links the women together.

Beauty cannot exist without fascination. Unless something captivates us enough to hold our interest for more than a fleeting moment, it’s pretty or pleasant or maybe lovely rather than beautiful. It’s why people we love become more beautiful to us the longer we love them; it’s why we find “flaws” beautiful on others. When I love someone, I’m quick to become fascinated by what fascinates them. Soccer, Slovenia, antipsychiatry, Montaigne, urban gardening. The other woman. It’s fascination once removed, but it is fascination nonetheless. I want to keep looking; my attention is held. This is part of what defines beauty. Is it any surprise that when I look at the various women I’ve been triangulated with—some against my will, some against my better judgment—I find beauty at every turn?

When I’ve been cheated on, occasionally friends have taken the tactic of beauty assassination in an attempt to assuage my grief. Girl could use some Clearasil. You’re pearls before swine, she’s pig slop. Or just: What was he thinking? I mean, look at her. I’m quite certain the same has been said of me when I’ve played the other role. You see the problem, don’t you? That using beauty as a lever in infidelity displaces the exquisite pain of betrayal? That Clearasil was a beauty in her way, and that Pig Slop was too, and that this is entirely beside the point? That to lament my own loss of appeal served only to prolong the lamentation of my loss of trust?

I’d like to think that my preternatural, private devotionals to the women I’ve been triangulated with are reciprocal in some way. Not that I want them find me pretty per se; it’s more that I want a sort of confirmation that I’m not the only one attempting to divert the pain of betrayal away from the accomplice and toward the betrayer, whatever side of emotional treason any woman might be on. But just as “girl talk” is a route to female connection only when each party is open to it, I now have to admit how much of my visual admiration of other women is one-sided. How much it’s about wanting them to see me: I wanted to stay in that ice cream parlor with my new boyfriend’s ex-girlfriend because I had nothing to offer her other than myself, and if she stayed there with me despite my rotten actions, it meant she saw something worth sticking around for. Inherent in being the other woman is a deep cynicism of men: You believe they always want something other than conversation, and this belief is played out with clandestine brushes against your knee beneath the dinner table. Women, though—at least women in these triangulated roles—have no such motivation.

* * *

What strikes me now about this weakness is not the way I felt toward the men involved, but toward the women. The spritely live-in girlfriend of a man I longed for and did not resist when he told me he shared my longing; the sloe-eyed designer whose partner told me had lost interest in sex with him years ago (of course!); the husky-voiced business major whose date slipped me a note at a party saying he wished he were there with me instead: These women intrigued me, and not competitively so. It would be easy to chalk this up to my own tendency to cast a golden light of admiration onto women in general. It would also be easy to chalk this up to being the other woman, not the—woman-woman? The girlfriend, the partner. The beloved, supposedly. When I tried to explain my bizarre reverence to a friend, she rolled her eyes. Of course you get to feel that way, she said. You won.

I’m resistant to attribute this sensation to “winning,” though, even under the faulty logic of other-womanness as winning, for it's happened when I’ve been the betrayed one too. I once discovered a stash of messages sent to my then-partner by a woman whose name I didn’t recognize, but who clearly knew who I was. Most of the content was your typical affair nonsense, but this was a woman who was thoughtful about me in the same sincere, curious, and egregiously self-involved manner that I’d had in past liaisons.

She’s prettier than I imagined, one of her messages went. My first thought was to wonder what she’d imagined me to look like, and whether my boyfriend had given her clues: She’s medium build/she’s brunette/she’s gotten thick in the waist. But her note continued: It makes me insecure. The admission had the effect of both a stab and a caress. A stab because as much as I hated the existence of this woman, I hated that she too used other women as mirrors that reflected back her doubts. I’d have preferred that she be superhuman, for then I’d have a receptacle for my vitriol that might have allowed me to stay with my boyfriend, whom I loved. And a caress because reading that she shared my own reaction—insecurity, shaky doubt, a plea for affirmation—did allow me to use her as a mirror, did let me see that whatever the reasons for his betrayal, it wasn’t because I wasn’t enough. If she was made insecure by my looks, and I by hers, that canceled each other out, right?, so the reason for the betrayal logically had to be something else. (Because logic and love go hand-in-hand so often, I know, I know.)

In tales of infidelity, we overlook a central fact: Two people share another. She and I already had two things in common—the man himself, and being the kind of women who would pique his interest. In another time, another place, another life, our begrudging sisterhood could have been sisterwives. We would live together, create a home together, prepare food together. I might braid her hair. And secretly, each of us would worry that the other would forever be more alluring to him, therefore—in my grief-stricken, abjectly depressed reasoning of the time—more alluring to all men, everywhere. How could I not be fascinated by her? I looked her up. She was beautiful.

There’s a particular way that someone you become intimately involved with knows you: They know a side of you that remains hidden to not only the public eye, but most private eyes as well. My best friend may know me better than most of my lovers have, but she’s never felt me grasp for her touch in the middle of the night, or seen me through the shaky moments that come after an act of, quite literally, naked vulnerability. What that means is that there are dozens of women roaming around who know those same things about the men who have entered my heart. Ex-girlfriends, ex-wives, yes, and I’ve been fascinated with them as well. But it is the other woman—the woman who knows not the man at age 19 or 27 or 38 or whatever age he has long passed, but the person he is now, the person who may have had dinner with you mere hours after a kiss good-bye with her—that you are actually sharing a person’s affection and attention with, in real time.

That’s what makes betrayal sear so acutely, of course. It’s also what links the women together.

* * *

When I’ve been cheated on, occasionally friends have taken the tactic of beauty assassination in an attempt to assuage my grief. Girl could use some Clearasil. You’re pearls before swine, she’s pig slop. Or just: What was he thinking? I mean, look at her. I’m quite certain the same has been said of me when I’ve played the other role. You see the problem, don’t you? That using beauty as a lever in infidelity displaces the exquisite pain of betrayal? That Clearasil was a beauty in her way, and that Pig Slop was too, and that this is entirely beside the point? That to lament my own loss of appeal served only to prolong the lamentation of my loss of trust?

I’d like to think that my preternatural, private devotionals to the women I’ve been triangulated with are reciprocal in some way. Not that I want them find me pretty per se; it’s more that I want a sort of confirmation that I’m not the only one attempting to divert the pain of betrayal away from the accomplice and toward the betrayer, whatever side of emotional treason any woman might be on. But just as “girl talk” is a route to female connection only when each party is open to it, I now have to admit how much of my visual admiration of other women is one-sided. How much it’s about wanting them to see me: I wanted to stay in that ice cream parlor with my new boyfriend’s ex-girlfriend because I had nothing to offer her other than myself, and if she stayed there with me despite my rotten actions, it meant she saw something worth sticking around for. Inherent in being the other woman is a deep cynicism of men: You believe they always want something other than conversation, and this belief is played out with clandestine brushes against your knee beneath the dinner table. Women, though—at least women in these triangulated roles—have no such motivation.

Since beauty functions as a code of connection between women, I turned to it as a sort of pass key to intimacy in times when my faith in the true nature of intimacy was shaken. After being betrayed myself, finding the other woman beautiful was a way of finding (concocting?) a trust that had been taken from me. And after helping someone else betray another woman, finding her beautiful was a misguided way of trying to reconcile the selfishness that landed me there in the first place with the way I wanted to relate to these women. I knew that somewhere inside me was a person with more respect for other women than my actions indicated, but at the time I didn’t have the character to allow that better instinct to thrive. The halo of beauty that I created was a paltry symbol of that instinct. It wasn’t enough.

With age and maturity (and therapy), I’ve learned to avoid situations that might find me turning these mental somersaults. This piece isn't a mea culpa; such opportunities are long gone. Opportunities for refocusing my efforts at emotional intimacy with other women remain, though, and it’s in the name of those opportunities that I’m trying to figure out why I’ve repeatedly returned to a different sort of gaze in the midst of infidelity. Perhaps when I felt so tethered to the male gaze myself, creating a female gaze and projecting it onto women I’d hurt (or been hurt by) was the only way I knew to express a true apology (or forgiveness). But apologies are only good if both parties speak the same language. And I don’t want anyone to be fluent in the tongue I was speaking back then.

Not long ago I discovered that Google logs all your searches, and that you can summon a historic tally of everything you’ve searched for when logged in. It’s been more than a decade since I last saw the woman I shared ice cream with, but in the seven years since I got my Gmail account, I’ve searched her name often enough that it’s the sixth-most-Googled term in my personal history. I have fantasized repeatedly about running into her. Each time, I look her in the eyes and say, I am sorry. Each time, a litany of excuses tumbles out: I was young, I was insecure, I was selfish, I was stupid. And each time, even in my fantasy, she walks away.

With age and maturity (and therapy), I’ve learned to avoid situations that might find me turning these mental somersaults. This piece isn't a mea culpa; such opportunities are long gone. Opportunities for refocusing my efforts at emotional intimacy with other women remain, though, and it’s in the name of those opportunities that I’m trying to figure out why I’ve repeatedly returned to a different sort of gaze in the midst of infidelity. Perhaps when I felt so tethered to the male gaze myself, creating a female gaze and projecting it onto women I’d hurt (or been hurt by) was the only way I knew to express a true apology (or forgiveness). But apologies are only good if both parties speak the same language. And I don’t want anyone to be fluent in the tongue I was speaking back then.

Not long ago I discovered that Google logs all your searches, and that you can summon a historic tally of everything you’ve searched for when logged in. It’s been more than a decade since I last saw the woman I shared ice cream with, but in the seven years since I got my Gmail account, I’ve searched her name often enough that it’s the sixth-most-Googled term in my personal history. I have fantasized repeatedly about running into her. Each time, I look her in the eyes and say, I am sorry. Each time, a litany of excuses tumbles out: I was young, I was insecure, I was selfish, I was stupid. And each time, even in my fantasy, she walks away.