What's going on in beauty this week, from head to toe and everything in between.

From Head...

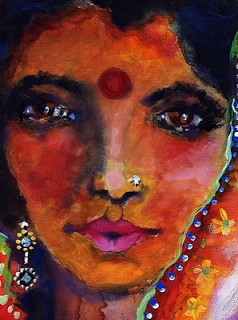

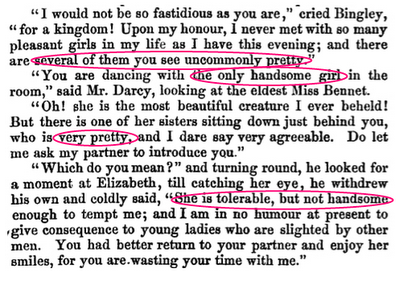

O Calcutta!: The Indian Institute of Technology is proposing distribution of nutrient-rich cosmetics to pregnant women in hopes of reducing infant mortality rates. And here I thought bindis just looked cool!

...To Toe...

Well-heeled: Because the "lipstick index" still isn't good enough, now we're wearing the economy on our feet. "Examining the trends alongside economic patterns led researchers to theorize that a shakier economic situation correlates with the popularity of similarly shaky high heels." The reporter sort of calls BS, though, thus giving me a girl crush on her. (Which doesn't take away from my girl crush on you, m'dear.)

...And Everything In Between:

They are the 1%: Step-by-step read on how the Lauder family has sheltered hundreds of millions of dollars over the years through skilled use of tax breaks. We're hearing so much about the 1% but it remains a vague idea to the 99% of us; this piece illustrates exactly how the 1% stays the 1%, and shows how it has nothing to do with our favorite bootstraps stories—like, say, a plucky daughter of Hungarian immigrants who cajoled her chemist uncle into helping her make a face cream to sell to her friends and eventually becoming one of the world's most influential cosmetics magnates. Sounds a lot more romantic than short sells on the stock market in order to maintain a neutral position under IRS rules and savings $95 million in capital gains taxes, eh?

I get so emotional: More insight into the emotions-cosmetics link, from a cosmetics marketing report being pimped out to companies. Manalive, I always like to think I'm one step ahead of companies, but that's foolish: "Beauty Attachment shows that for certain consumers, beauty is extremely important and they’d rather skip breakfast than skip their morning routine; while for others, it’s simply a utility that meets a need, like a front door key.... Simply put, some women see the aisles at Sephora and their head spins with anticipation; while others see these same aisles and become incredibly anxious." Girl, they have got your number.

Hungry lies: Lionsgate, the studio putting out Hunger Games, is being sued by a cosmetics company for breach of contract surrounding an exclusive Hunger Games nail polish line.

Not so kawaii: I didn't realize until reading this piece about Shiseido vice president Kimie Iwata that Japanese professionals were even more imbalanced than Americans: Women account for less than 1% of top-level Japanese business executives.

Everyone I Have Ever Bathed With: Unfortunately late on this, but Tracey Emin soap!

Playing dirty: Beauty/body product chain Lush is taking action against a UK politician whose environmental policies have been deemed lacking. In the States it's relatively rare to see a company so specifically target one politician, much less a "softball" company like a cosmetics purveyor. I've got to hand it to Lush—this doesn't really seem like a publicity stunt to me (or is that the point?).

Political wrinkle: Australian prime minister Julia Gillard under fire for accepting anti-wrinkle creams as gifts, even as she refused other designer wares. (Really, the buried lede here is that the prime minister has a partner, and has never been married. As an American, to me this seems like some future-world sci-fi Ursula Leguin utopia. A woman is leading the country and we all know she has sex without the legal bond of marriage?!)

Can't decide which is more awesome: Collection of historic depiction of muscular women, or collection of Ugly babies in Renaissance art. ("I love you both, just in different ways!") (Thanks to Lindsay for the tip)

Photoshopped: With a new tool that allows us to tell how much a photo has been digitally altered, is it possible that we'll someday have "retouch ratings" like we do movie ratings? "Rated three points for rib removal and jawline trimming."

Framed: Bitch magazine has two particularly interesting "In the Frame" entries this week: A photo of noted photographer Nan Goldin one month after being battered, in which her makeup contradicts the idea of the hidden, cowering victim, and then the art of Ingrid Berthon-Moine, showing women wearing their menstrual blood as lipstick. (And here I thought I was a hippie for trying out beets as lipstick, as per No More Dirty Looks.)

The importance of being intact: Oscar Wilde's restored tomb makes its debut in Paris, covered by a glass partition to protect it from "being eaten away by lipstick," as is tradition.

Paging Don Draper: South African fragrance line Alibi is designed for cheating spouses to wear to literally put suspicious partners off their scent trail. "I Was Working Late" smells of cigarettes, coffee, ink, and wool suits; "We Were Out Sailing" features sea salt and cotton rope. I am not making this up. (But they might be; I can't find anything about the company elsewhere. Hmm.)

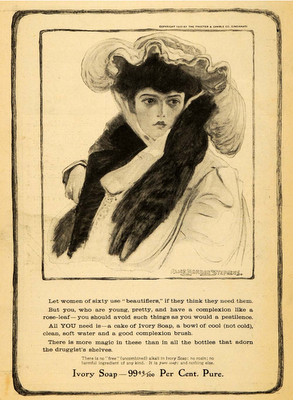

Sweet smell of success: The odiferous history of "perfume" versus "cologne" in regards to becoming a comment on a man's sexual orientation, and what the headily scented Liberace had to say about it.

Neat and clean: Half of the men in Britain don't think it's necessary to be clean-shaven to look well-groomed. (I heartily agree, as a fan of a bit of scruff on a feller.)

This week in dead movie stars: Why Marilyn Monroe is still a beauty icon, and did you know that Hedwig Eva Marie Kiesler—aka Hedy Lamarr—invented a telecommunications process that's still used today in much of our wireless communication?

Newly inquired: If you enjoy my more academic-ish posts on here, you should definitely check out The New Inquiry. I'm proud to be associated with them, and prouder still of their profile in this week's New York Times! (Quibble: I wouldn't call any of these minds those of "literary cubs"; all parties involved are far too insightful and thought-provoking for that.)

Attention Sassy lovers: Former Sassy editor Jane Larkworthy, now beauty director at W, is featured on Into the Gloss this week. "I do think [beauty products] should be done in an accessible way, though—I don’t ever want beauty to be intimidating."

Hair mayonnaise: Hysterical beauty bit from comic Sue Funke, courtesy Virginia.

Fight for the right: This piece at Rookie about cultural stereotyping is worth reading in its own right, but of particular interest to me is the collection of vintage photos of "black and brown and yellow girl gangs in American history" on the second page, all from Of Another Fashion. The photos of beaming, well-dressed Japanese women heading off to internment camps during one of the most shameful episodes of U.S. history raises questions about expectations of femininity, and of fashion's true role in our lives: "Even during internment, these girls were determined to look cute. And though that may sound like the height of triviality, it’s not. As the late, great civil-rights activist Dorothy Height once said, 'Too many people in my generation fought for the right for us to be dressed up and not put down.'"

Honored: I love Sally's concept of "honoring your beauty," and I'll throw in that once I learned that the way to accept a compliment was to look the person in the eye, smile, and say, "Thank you," I felt like I'd learned something small but important. It also made it easier to give a compliment too; I stopped worrying that every compliment I gave was loaded somehow. There's no hidden motive. I really just like your hair.

Push it good: This post from Fit and Feminist on the myth of the noncompetitive female made me (and her, as evidenced by her Mean Girls reference) wonder why we embrace totally contradictory views of women and competition. C'mon, patriarchy: Are we all cooperative sweethearts who aren't so great at team sports because we just want to hold hands and make daisy chains, or are we vindictive bitches who love to tear one another apart? Just tell us already, my best bitches and I are getting tired of this sewing circle-Fight Club jazz.

Indian Woman With Red Bindi, Ginette Fine Art (no word as to whether model was great with child)

From Head...

O Calcutta!: The Indian Institute of Technology is proposing distribution of nutrient-rich cosmetics to pregnant women in hopes of reducing infant mortality rates. And here I thought bindis just looked cool!

...To Toe...

Well-heeled: Because the "lipstick index" still isn't good enough, now we're wearing the economy on our feet. "Examining the trends alongside economic patterns led researchers to theorize that a shakier economic situation correlates with the popularity of similarly shaky high heels." The reporter sort of calls BS, though, thus giving me a girl crush on her. (Which doesn't take away from my girl crush on you, m'dear.)

...And Everything In Between:

They are the 1%: Step-by-step read on how the Lauder family has sheltered hundreds of millions of dollars over the years through skilled use of tax breaks. We're hearing so much about the 1% but it remains a vague idea to the 99% of us; this piece illustrates exactly how the 1% stays the 1%, and shows how it has nothing to do with our favorite bootstraps stories—like, say, a plucky daughter of Hungarian immigrants who cajoled her chemist uncle into helping her make a face cream to sell to her friends and eventually becoming one of the world's most influential cosmetics magnates. Sounds a lot more romantic than short sells on the stock market in order to maintain a neutral position under IRS rules and savings $95 million in capital gains taxes, eh?

I get so emotional: More insight into the emotions-cosmetics link, from a cosmetics marketing report being pimped out to companies. Manalive, I always like to think I'm one step ahead of companies, but that's foolish: "Beauty Attachment shows that for certain consumers, beauty is extremely important and they’d rather skip breakfast than skip their morning routine; while for others, it’s simply a utility that meets a need, like a front door key.... Simply put, some women see the aisles at Sephora and their head spins with anticipation; while others see these same aisles and become incredibly anxious." Girl, they have got your number.

Hungry lies: Lionsgate, the studio putting out Hunger Games, is being sued by a cosmetics company for breach of contract surrounding an exclusive Hunger Games nail polish line.

Not so kawaii: I didn't realize until reading this piece about Shiseido vice president Kimie Iwata that Japanese professionals were even more imbalanced than Americans: Women account for less than 1% of top-level Japanese business executives.

Everyone I Have Ever Bathed With: Unfortunately late on this, but Tracey Emin soap!

Playing dirty: Beauty/body product chain Lush is taking action against a UK politician whose environmental policies have been deemed lacking. In the States it's relatively rare to see a company so specifically target one politician, much less a "softball" company like a cosmetics purveyor. I've got to hand it to Lush—this doesn't really seem like a publicity stunt to me (or is that the point?).

Political wrinkle: Australian prime minister Julia Gillard under fire for accepting anti-wrinkle creams as gifts, even as she refused other designer wares. (Really, the buried lede here is that the prime minister has a partner, and has never been married. As an American, to me this seems like some future-world sci-fi Ursula Leguin utopia. A woman is leading the country and we all know she has sex without the legal bond of marriage?!)

Reached a compromise: Historic depictions of ugly muscular babies. Vermeyen, Holy Family

Can't decide which is more awesome: Collection of historic depiction of muscular women, or collection of Ugly babies in Renaissance art. ("I love you both, just in different ways!") (Thanks to Lindsay for the tip)

Photoshopped: With a new tool that allows us to tell how much a photo has been digitally altered, is it possible that we'll someday have "retouch ratings" like we do movie ratings? "Rated three points for rib removal and jawline trimming."

Framed: Bitch magazine has two particularly interesting "In the Frame" entries this week: A photo of noted photographer Nan Goldin one month after being battered, in which her makeup contradicts the idea of the hidden, cowering victim, and then the art of Ingrid Berthon-Moine, showing women wearing their menstrual blood as lipstick. (And here I thought I was a hippie for trying out beets as lipstick, as per No More Dirty Looks.)

The importance of being intact: Oscar Wilde's restored tomb makes its debut in Paris, covered by a glass partition to protect it from "being eaten away by lipstick," as is tradition.

Paging Don Draper: South African fragrance line Alibi is designed for cheating spouses to wear to literally put suspicious partners off their scent trail. "I Was Working Late" smells of cigarettes, coffee, ink, and wool suits; "We Were Out Sailing" features sea salt and cotton rope. I am not making this up. (But they might be; I can't find anything about the company elsewhere. Hmm.)

Sweet smell of success: The odiferous history of "perfume" versus "cologne" in regards to becoming a comment on a man's sexual orientation, and what the headily scented Liberace had to say about it.

Neat and clean: Half of the men in Britain don't think it's necessary to be clean-shaven to look well-groomed. (I heartily agree, as a fan of a bit of scruff on a feller.)

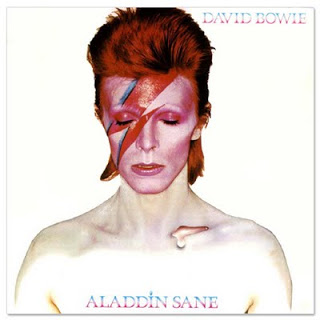

Inventor Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler

This week in dead movie stars: Why Marilyn Monroe is still a beauty icon, and did you know that Hedwig Eva Marie Kiesler—aka Hedy Lamarr—invented a telecommunications process that's still used today in much of our wireless communication?

Newly inquired: If you enjoy my more academic-ish posts on here, you should definitely check out The New Inquiry. I'm proud to be associated with them, and prouder still of their profile in this week's New York Times! (Quibble: I wouldn't call any of these minds those of "literary cubs"; all parties involved are far too insightful and thought-provoking for that.)

Attention Sassy lovers: Former Sassy editor Jane Larkworthy, now beauty director at W, is featured on Into the Gloss this week. "I do think [beauty products] should be done in an accessible way, though—I don’t ever want beauty to be intimidating."

Hair mayonnaise: Hysterical beauty bit from comic Sue Funke, courtesy Virginia.

Fight for the right: This piece at Rookie about cultural stereotyping is worth reading in its own right, but of particular interest to me is the collection of vintage photos of "black and brown and yellow girl gangs in American history" on the second page, all from Of Another Fashion. The photos of beaming, well-dressed Japanese women heading off to internment camps during one of the most shameful episodes of U.S. history raises questions about expectations of femininity, and of fashion's true role in our lives: "Even during internment, these girls were determined to look cute. And though that may sound like the height of triviality, it’s not. As the late, great civil-rights activist Dorothy Height once said, 'Too many people in my generation fought for the right for us to be dressed up and not put down.'"

Honored: I love Sally's concept of "honoring your beauty," and I'll throw in that once I learned that the way to accept a compliment was to look the person in the eye, smile, and say, "Thank you," I felt like I'd learned something small but important. It also made it easier to give a compliment too; I stopped worrying that every compliment I gave was loaded somehow. There's no hidden motive. I really just like your hair.

Push it good: This post from Fit and Feminist on the myth of the noncompetitive female made me (and her, as evidenced by her Mean Girls reference) wonder why we embrace totally contradictory views of women and competition. C'mon, patriarchy: Are we all cooperative sweethearts who aren't so great at team sports because we just want to hold hands and make daisy chains, or are we vindictive bitches who love to tear one another apart? Just tell us already, my best bitches and I are getting tired of this sewing circle-Fight Club jazz.