Today's word post is kindly being hosted at Plus Size Models Unite, which features interviews (and stunning photos) with plus-size models, shedding some light on the industry. I wrote a post for them about the history of the term "plus-size," which was fascinating to research. (I was particularly amused by Lane Bryant's early use of the term "junior plenty," which I guess was phased out by my day. All I remember of shopping during my pudgy girlhood was "6X"—any other 6X-ers in the house?) Here's some of what I learned (you can read the whole thing here):

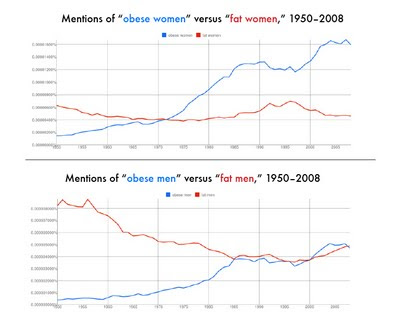

It wasn’t just consumers who were coming up with weird terms to describe ladies of size. Women’s magazines in the 1970s gave style advice to readers who were “chunky,” “bigger,” “broad,” “big-boned,” “heavier,” and “fat.” Even a lifestyle and fashion magazine devoted to plus-size women, Big Beautiful Woman, didn’t embrace the term until after its 1979 launch. By the 1980s the word choices had become a tad more complimentary: “round” and “full-figured” began cropping up, along with “curvy all over,” particularly a favorite in annual June swimsuit roundups.

_________________

Elizabeth Nord, one of the brains behind Plus Size Models Unite, also runs Secrets of Moms Who Dare to Tell All. The blog touches on everything from recipes to handling overcommitment to navigating motherhood in the midst of mean girls. Here she is with tips for you on what to do on those days when you feel utterly blah. Enjoy! (This post originally appeared on Secrets of Moms, but as this child-free blogger can attest, toddlers aren't the only things that can make you feel frazzled...)

Elizabeth, post-frazzle, all fabulous.

I know firsthand what it feels like to transition from feeling frazzled and frumpy to feisty and fabulous! After having our kids, there have been many times when I have felt exhausted, let myself go, or lost my fire. Here are some ways I’ve gone from frazzled and frumpy to feeling feisty, strong, sexy, and fabulous!

• Set boundaries and reclaim yourself. We are busy women trying to balance kids, marriage, friends, careers, domesticity, and personal time. Do not underestimate the power of “you” time. Some of us may feel guilty taking time out for ourselves (I do), but work through it or you will end up burned out and resentful. If you take time for yourself, you will feel refreshed, be a happier mom and wife, and better able to take on the world.

• Throw your shoulders back, pick up your chin, and open up your posture. Yes, do it right now! How does that feel? It feels good! I immediately feel more confident and energetic whenever I extend my arms. If I’m sitting down somewhere and notice that I’m not feeling “on,” I just open up my posture by setting one of my arms on the chair next to me. I swear it works wonders every time!

• Embrace your body right now! I have been really open on both my web sites about the fact that I’m not very well endowed, and I’ve decided–who cares!?! Feeling successful and sexy is not about a cup or dress size; it’s about being confident with who you are right now. I’ve got a lot more going on than my chest size, so I’ve decided to focus on what I do have. That change of attitude has been positively life altering for me!

• Ditch the baggy sweats and frumpy clothes. Get rid of outdated deformed bras and old panties too. I’m not saying you need to wear a low-cut blouse and super short tight skirt to feel sexy. No—I’m saying find something comfortable and classy that accentuates what you love about your body. Have fun with it!

Several years ago, a clothing boutique owner explained to me and showed me what styles would work for my body type. His advice was invaluable. It made me think about my clothing choices and the lines of my silhouette very differently. One of my friends met with a personal stylist at Nordstrom’s and it was an amazing experience for her that had a profound impact on the way she feels about her body. She had not embraced her curves until she learned how to use clothing to flatter her figure. Regardless of what your body type is, you can find the perfect clothing for you!

• Change it up! Find a different route to work, your kids’ school, or when you are running or walking. Try a completely new mani/pedi color or design that you would not normally wear. It’s fun to step away from the usual. Visit a new stylist to get different hairstyle or color ideas. It’s interesting to hear a new stylists ideas, whether it’s dramatic or subtle. I had my eye brows professionally shaped several years ago, and it was an amazing experience. I know it sounds basic, but I didn’t know how to make the most of my features and she did! It made such a difference, and I felt beautiful! If in doubt, go to an expert.

• Eat well. I love food—LOVE it! I’ll eat almost anything. Even though I eat whatever I want, I don’t go crazy because I know I’ll feel like crap if I eat a bunch of chips, burgers, fries, and Hostess Donuts in excess. It zaps my energy and I feel sluggish. I love the way I feel after eating a healthy diverse meal. I’m not saying don’t eat what you want, I’m just saying—moderation is key!

• Go exercise. It could be a walk, run, aerobics, yoga, swimming, dancing, kick boxing, or whatever—get your body moving and get your blood pumping. It’s good for your mind, body, and soul! I always eat better when I am physically active, and I feel way sexier, stronger, and energetic too!

• Laugh often! When I ‘m feeling funky, I know I need to change my perspective and attitude by looking at things from a different angle. Sometimes I call one of my friends, Angela, and say whatever I’m thinking without censor, which usually means me talking crazy talk. Then she joins in with the crazy talk, and we always end up laughing hysterically. It’s hilarious! That always helps to diffuse any negativity I’m feeling. Boxing via the Wii is fun and makes me giggle too, and I burn off the funky energy while I’m playing!

• Be brave! Let your authentic unique personality shine and embrace who you are truly meant to be. Believe in yourself. Take care of yourself. Be fearless. Take charge. Set goals and go after your dreams. With the right mindset, you can succeed, feel great, and accomplish anything!

Please share your ideas. How do you get yourself out of a funk and back on track?