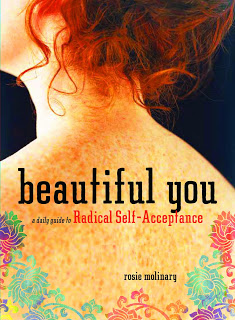

I came across the book Beautiful You serendipitously, one of a few stray review copies at a magazine where I worked at the time. I’ve read plenty of “you go, girl!” works designed to increase self-acceptance, but what sets Beautiful You apart is its day-by-day actionability. Day 50: “Ask others to define beauty.” Day 192: “Lift weights.” Day 268: “Give flowers.” Some exercises launch enormous mental projects, of course (Day 114: “Let go”), but the book is a concrete, meditative guide to getting at the root of what makes so many women feel not-so-great about their appearance.

Its author, Rosie Molinary, also penned Hijas Americanas: Beauty, Body Image, and Growing Up Latina; in addition, she’s a speaker, teacher, activist, and mother. Her own stories shine through in Beautiful You; by the time we actually spoke, I felt as though I were hearing a familiar, generous voice, one as mellifluous as her words (but with the faintest Carolina twang). We talked about the beauty of the unattainable, the reason Latinas get a disproportionate amount of plastic surgery, and why to get a professional bra fitting. In her own words:

On the “Latina Mystique”

One of the things that has been emphasized over the years with beauty is searching for the unattainable. When I was growing up, there weren’t any Latinas in the media, so there wasn’t something anybody could consider to search for. The unattainable we were searching for was being tall, thin, and blonde. But in the last 10 years, there have been Latinas more prominently in the media—which, for those who aren’t tan or dark or what’s often called “exotic,” has created a craving for that. We covet beauty as what we literally can’t attain.

I wrote Hijas in my early 30s, and I was talking to women in their late teens and early to mid-20s about Latinas in the media. When I was 18, if I said to someone I was Puerto Rican, they’d say, “Puerto what?” I grew up in South Carolina, and there weren’t other Latinas around. So I thought these women were going to say that it was so much easier to come of age now when there were Latinas in the media—and that ended up not being the reaction at all. Instead, they talked about how it created a really hard standard for them. I was getting “Puerto what?”, but fast-forward to young women now, and if they say they’re Puerto Rican and happen to be Afro-Latina, so they’re black Puerto Rican, people are like, “Why don’t you look like Jennifer Lopez?” Because in the media there’s a bit of a poster girl for each country. You’re Mexican, it’s Salma Hayek; you’ve got Jennifer Lopez for Puerto Rico, Eva Mendes for Cuba. If you’re African American, there’s not just one African American actress to compare you to; if you’re white, there’s not just one white woman to be compared to.

On the Pain and Effort of Beauty

Something I didn’t know before researching Hijas was that Latinas get the most plastic surgery of any subgroup in the U.S., which is interesting because Latinas are not the wealthiest minority in the U.S. There’s a lot of discretionary dollars being spent on something that seems optional for someone who doesn’t have a lot of discretionary dollars. I talked about this with the head of plastic surgery at the University of Kentucky, who happens to be Latin American. And he said—I’m paraphrasing—that Latina women are aware that beauty takes effort, and that it’s not painless. He said something along the lines of: When I have a client come in from any background that’s not Latina, it’s 50/50 as to whether they’re going to get the surgery. But if I have somebody who’s Latina who’s already made this appointment with me for a consultation, there is nothing I’m going to tell them about the pain or recovery that will talk them out of it. Latina women are ultimately always aware that beauty is a sacrifice.

The other interesting thing he said was that he felt Latina women were more willing to own up to the effort. You might run into a woman of a non-Latina background and say she looks great, and she’ll say, “Oh, I just threw myself together this morning,” like it’s this effortless perfection. But if you run into a Latina woman and say, “You look really nice,” her reaction will be, “Oh, thanks! I worked overtime to buy this dress, I’ve got on this girdle, it took me three hours to get my hair like this.” She’ll own up to the effort, because part of it is wanting people to know they thought this event warranted that effort and respect. I see some truth in that.

On Knowing But Not Believing

When I interviewed women for Hijas, I asked what they thought was beautiful. And to a person, they would say: confidence, being kind, helping others, loving others. In general, no one said anything physical in their definition of beauty! Then I would ask, “Do you consider yourself beautiful?” and they would say, “Who, me? Oh, no, no, I’m not beautiful.” Now, 30 minutes earlier, they were talking to me about how passionate they were as a schoolteacher, or how much they championed their younger sister. There were all these earlier references that indicated to me they matched their definition of beauty. I would lay this out to them, and I had several women after our conversations—I probably interviewed 100 women and 12 to 15 e-mailed me later about this—say, “It was significant to me that you pointed out the inconsistency in how I view myself and how I view others.”

Women are raised to be demure and to deflect. And we aren’t really allowed to be gracious about ourselves. Often we’re raised not to just be good girls; we translate that into being perfect girls. So it’s not okay for us to judge ourselves on these gracious standards that we give others—we need to be higher than that standard. And it’s paralyzing, because what can happen is that we believe that if some aspect of our physicality changes, then we’ll finally be happy. And the truth is, a negative body image isn’t only about how you feel about your body. It’s rooted in so much more, and unless you deal with those things, you’re going to be unhappy no matter how long your hair or how much you weigh.

But there’s a comfortable storyline in existing in what you’ve always believed. You know how it’s going to play out, you know what it means you can do, what you can’t do. All the choices are clear. So what happens when someone says—and this isn’t exactly what I’m saying, but it’s a part of it—if you feel bad about yourself, you’re making a choice to feel bad about yourself. What I’m inviting you to do is not make that choice anymore. Then all of the answers can be different, and how do those things play out? And that’s hard, because it’s the unknown. But it’s also ultimately the most satisfying place you can land.

On the “Beautiful You” Exercises

There aren’t that many appearance-oriented things that are important to me. But I do have some exercises in Beautiful You that are appearance-oriented. [Examples: Visit a makeup artist, get a professional bra fitting, get a haircut.] For some women those things reflect self-care, and that’s been part of the volition of some women—increased disposable income and what to do with that. I didn’t want to leave out those women from the Beautiful You journey. And I have my moments too—I had my first professional adult bra fitting a few years ago, and it made a significant difference in how my clothes felt. It had a really positive effect on me, and I hadn’t expected that; I just needed a bra and this woman came in and was like, “You need to try this,” and I was like, “Oh my god, that is what I need to try!” There are areas where we could use somebody who knows a little bit more than we do.

That said, I don’t think that every single day is a fit for every single woman. I think it’s okay to make the book a choose-your-own-adventure book. But I think it’s important that if you’re particularly resistant to something that you do it, because there’s a reason you’re resistant to it, and you can get a bit of insight.

On Day 73: “Use Something You’ve Been Saving for a Special Occasion”

I have this beautiful, expensive purse. I didn’t feel my behaviors warranted such a beautiful or expensive piece in my life—I’d literally used it twice. And finally one day I looked at it in this little bag gathering dust, and was like, “This is the most absurd thing. I have this beautiful thing...in my closet.” What’s the point of having a nice thing if you’re not going to enjoy it? Too often we deny ourselves pleasure. And part of recognizing beauty is experiencing pleasure. Sometimes pleasure is as simple as taking something out to enjoy that you don’t typically let yourself enjoy. What was that about, with my purse? Why was I punishing myself? Why wasn’t I worth it? Now I don’t take it out if it’s raining, but if I’m wearing certain outfits I am rocking that bag.

On Her Definition of Beauty in 25 Words or Less

Giving and experiencing love. I think I have 21 words left? But that's it for me.